|

|

| Date Published: |

L’Encyclopédie de l’histoire du Québec / The Quebec History Encyclopedia

The Fight for Oversea EmpireThe Seven Years WarWilliam Pitt Takes Over in England

[This text was written by William WOOD and was published in 1914. For the precise citation, see the end of the document.] A NEW IMPERIAL FORCE

TOWARDS the end of 1757 Frederick the Great checked the apparently overwhelming forces against him at Rossbach and Leuthen. In the following summer he beat back the Russians at Zorndorf ; and though he lost to the Austrians at Hochkirchen in October he finished the campaign by a triumphant march through Silesia. Acting with restless energy and consummate skill on interior lines he moved rapidly from point to point, preventing his slower enemies, who acted on exterior lines, from combining to crush him. Ferdinand of Brunswick drove the French out of Hanover and defeated them in June at Crefeld. Thus the enemy were everywhere swept back beyond the German frontiers they had so often overrun.

But

the greatest influence brought to bear on the worldwide issues in 1758

was Pitt's accession to settled power. When in office before, during

the winter of 1756-57, he had dismissed the foreign mercenaries, increased

the militia, raised the Highland regiments, and given the country a

glimpse of what imperial statesmanship really ought to be. But it was

not until 1758 that he was able to exert a continuous control on the

war. His great administration lasted four years, from June 29, 1757,

to October 5, 1761. He had his faults : a certain theatricality of manner,

a too visible contempt for the common cry of politicians, and a too

purely vindictive attitude towards the Bourbons ; but as a great war-statesman

he was, and remains, unrivalled. History makes much of the bad beginning

and worse ending of the Seven Years' War. But Pitt was out of power

on both occasions.

Next to Pitt came Anson, good as a fighting admiral, but better as first lord. When he chose Anson, Pitt ignored those trammels of party which are such stumbling-blocks to the mere politician, and he gloried in it. 'I replaced Lord Anson at the Admiralty, and I thank God that I had resolution enough to do so.' Anson made two mistakes : he appointed Byng and failed to foresee that Spain was joining France in 1762. In all else, from desk to dockyard, from selecting the model of a single ship to combining the strategy of battle-fleets over the whole world, he splendidly excelled. He had the principal hand in the headquarters work of the first regular system of blockade, the destruction of the French invasion transports at Havre, the fleet-actions at Lagos and Quiberon, and the capture of Louisbourg, Quebec, Montreal, Martinique, Manila and Havana. Even more important was his remarkable faculty for bringing the best executive men to the front ; among them seven first-rate admirals - Hawke, Boscawen, Osborn, Saunders, Rodney, Howe and Keppel. Two other famous sea-fighters also owed him their first commissions, the Earls of St Vincent and Camperdown.

The army could count on no such handling as this - and indeed its need was less, for its opportunities were more restricted. But Ligonier was a capable commander-in-chief, and George ii knew what soldiering means in peace and war.

Pitt could not change the whole face of the war at once ; but he confirmed his policy of subsidizing Frederick for the great campaigns on land, while he devoted the British army and navy to united-service work designed to distract Frederick's enemies in Europe and ensure British imperial expansion overseas. The merchant navy was fast increasing British prosperity, as the mercantile community gratefully acknowledged later on; while the fighting navy, to which it owed its security, was fast destroying its rival, capturing all that was left of the French merchantmen, and 176 neutrals with French cargoes. Pocock was fighting d'Aché in the East, where Clive had turned the tide of war the previous year at Plassey, and d'Aché, though he held his own in battle, crawled home exhausted, because British sea-power had made the sea a desert to all its enemies. Senegal and Goree fell in Africa ; Cherbourg in France itself. Even Russia and Austria began to feel the weight of hostile British sea-power. And meantime the navy that was doing all this in the Old World was also destroying the forces that might have aided the French cause in the New. A French fleet was shut up in Cartagena before the year began. Duquesne went to help it out, but lost his own squadron instead. And du Chaffault, who reached Isle Royale, had to go on to Quebec to keep his fleet in being. In France the pressure of British sea-power was beginning to tell on every department of life, while in Canada it was already beginning to exert that constricting death-grip which it never relaxed till the whole colony surrendered at Montreal .

CORRUPTION IN OFFICIAL LIFE

Bigot belongs more to the general history of Canada than to that of the Seven Years' War. But it must be remembered that when he was preying on her vital resources he was weakening her, in a military sense, quite as much from the inside as the British navy was from without. Of course he had accomplices, and the whole vampire brood together flocked round the prey more greedily than ever when they saw that a British conquest might take it out of their clutches. As this disaster grew more and more imminent, at a time when even the lax French government was beginning to watch them, they mostly welcomed the catastrophe; in the hope that individual misdeeds might be covered up in universal ruin. Vaudreuil was not among these chartered brigands, but he condoned them. He approved scandalous contracts for the commissariat and transport, for useless fire-ships, bad ammunition and worse forts; and he was the official commander-in-chief. There stand his acts and words against him, to damn him for ever at the bar of history. Very different were Montcalm, his lieutenants, and nearly all his officers and men, as well as the Canadian habitants and priests. The sword and cross led well, through those last dire years, and the people followed faithfully, according to their lights and in spite of the paralysing misery of their condition. But in Canada everything which, under self-government, would be called 'politics' and civil service was rotten to the core.

BRITISH DISASTER AT TICONDEROGA

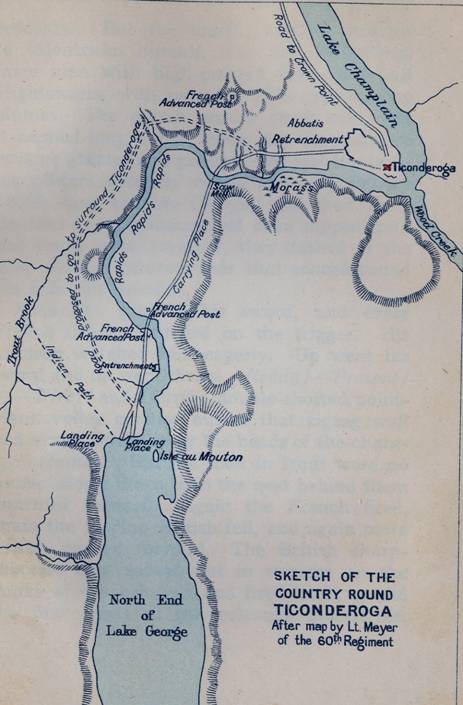

The British plan of campaign was the old one of simultaneous attacks on the French flanks and centre. Louisbourg and Fort Duquesne were to be destroyed, while the centre was to be driven in along the line of Lake Champlain.

Montcalm's advice was to concentrate at Ticonderoga. But Vaudreuil insisted on sending his brother with Lévis to make a useless 'diversion' towards Oswego. The French were weak enough as it was. Provisions and transport were both so scarce that the regulars had to be widely scattered among the habitants for the winter, and fed on half-rations of horse-flesh. The generals ate the same fare ; but Bigot and his myrmidons lived in luxury on the best of the food intended for the colony. The regulars, underfed as they were and necessarily slackened in drill and discipline by their long stay in scattered winter quarters, yet once more answered the call to arms as readily as ever. The militia were not available, partly because some of them had gone on Vaudreuil's wild goose chase towards Oswego ; partly because others took the alternative of exemption, on condition of carrying Bigot's goods about the country free ; partly because some had to remain at home if there was to be any harvest, and partly because Vaudreuil, in order that he might keep the soldiers under his own orders as long as possible, would not let Montcalm have those who really were available. Thus Ticonderoga, to Vaudreuil's subsequent disgust, became a victory won mainly by the French regulars. To complete his spiteful interference Vaudreuil issued such ambiguous orders that Montcalm found himself deprived of all initiative while charged with all the responsibility - especially in case of failure. A personal interview followed, and Vaudreuil, frightened by his own ineptitude, signed new orders drafted by Montcalm himself. Much time was lost by all these vexatious delays, and it was only on June 24, within a fortnight of the battle, that Montcalm could leave Montreal for the front. On the 30th he entered Ticonderoga, where he found his eight battalions reduced to 2,970 men to the many good men who had been sent off towards Oswego, and the many bad recruits he had been obliged to leave behind. Provisions and fortifications were in still worse condition. The intendance and civil contractors were responsible for both.

Yet Ticonderoga was an excellent position, and Montcalm made the most of it. It stood on a small peninsula, commanding the only open waters to the north, and the nature of the surrounding country was such that no army could advance by any other route. The peninsula projected about three-quarters of a mile, and its neck was about the same distance across. The fort, not too well gunned, was garrisoned by one battalion. The remaining seven were entrenched across the left half of the neck, which was high ground, with the flanks curved back at right angles to the front. The right flank ran back to within 600 yards of the fort, and the two were connected by the straight line of the height of ground which ran from this flank to the fort. The right was further protected by having a clear line of fire cut through the woods to the right of the fort, and by an entrenchment protecting the right rear of the main position. The British were so many and the French so few that the situation seemed desperate. But a week's incessant hard work wrought a wonderful change. The officers used axe and rope to encourage the men. A continuous abattis of trees, with their sharpened branches pointing outwards, ran completely round the thousand yards of entrenchment manned by 3000 French regulars. Including the 451 Canadian regulars and militia, and the 200 more who joined during the action, with the garrison of the fort, Montcalm had barely 4,000 men all told, from first to last. The gallant Lévis joined only the night before the battle, which he nearly missed altogether, owing to the absurd' diversion against Oswego, on which Vaudreuil had thrown him away.

Meanwhile Abercromby was advancing with four times as many men. On the morning of the 5th, a calm and cloudless day, more than a thousand boats began their journey up beautiful Lake George , just as the sun rose above the forest-clad hills. Never had such pageantry of war appeared in all America. In the centre 6,000 regulars, resplendent in scarlet and white and gold, on the flanks 9,000 provincials in dense clusters of blue, and in rear bateaux and double flatboats, platformed for the artillery and train. Thousands of oars gleamed in the sunlight, the very air was vibrant with music, the rolling drums woke every echo, and, piercing the other sounds, the pipes of the Black Watch screamed Highland defiance at the foe.

Abercromby had learnt nothing since coming to America. But the young second-in-command, Lord Howe, was both the head and heart of the whole army. Wolfe called him the noblest of Englishmen and the best soldier in the army, and Pitt himself said he was a complete model of the military virtues. Unluckily for the British, he fell in the first preliminary skirmish. Abercromby had now to think for himself. He sent out an engineer, who foolishly reported that the abattis could be taken by assault. He then advanced his infantry and left his artillery behind. He tried one diversion, by some boats, against the French left, but the guns of the fort and the nearest French infantry, who immediately lined the shore, soon drove back this party.

In the great attack there were 14,000 against 4,000 ; but of these only the regulars came to close quarters, 6,000 against 3,000. The 8,000 provincials lined the edge of the clearing which Montcalm had made, two hundred yards wide, all round his position. The four assaulting columns of redcoats were formed up just after noon, a single gun fired from the fort gave the signal for the French to drop their tools - they were working till the last minute - and take up their muskets: and the battle began. The first rush looked as if it must carry all before it. But the heads of the columns got entangled in the abattis, and were mown down by point-blank musketry from the entrenchments, where Montcalm had one man for every foot of frontage. Again and again the attack was renewed ; again and again it surged back, like the waves of a stormy ebb, angrily leaving the wreckage on the shore. All that hot, still, midsummer afternoon the British columns beat in vain against Montcalm's magnificent defence. During a lull in the firing some of his men, who knew why Vaudreuil had withheld the reinforcements, were overheard saying, 'The governor has sold the colony, but we won't let him deliver it.' At last Abercromby, who never came near the firing-line, ordered a final effort. It was as gallantly made and met as the others. He then drew off, went back to his boats, and was soon completely out of touch with his victorious enemy. The British loss was nearly 2,000. The regulars lost twenty-seven per cent of their own numbers, the provincials only four.

Vaudreuil sent reinforcements when their usefulness was gone, wrote new ambiguous orders, and began to claim the victory for the militia. As they numbered only 450 at the beginning of the battle and only 200 more at the end, and as their loss was only four per cent compared with the French twelve, it is manifestly absurd to suppose that this one-seventh of Montcalm's army had any claims to distinction comparable to those of the other six-sevenths. The total French loss was exactly 400, only one-fifth as much as the British.

Montcalm had been again victorious. But he was sick at heart. 'What a country,' he wrote home, 'where rogues grow rich and honest men are ruined.' His emoluments were insufficient from the first. Now that corruption and hostile sea-power had sent prices up tenfold, he saw himself getting hopelessly into debt, along with every other honest officer around him. The reward that he and they would have liked best of all would have been their recall to France. He did, indeed, write for his. But he soon heard news of disaster elsewhere, which made him volunteer to stay at his post till the end.

THE TURNING POINT OF THE WAR

Louisbourg in 1758 Louisbourg was garrisoned by about 3,000 effective troops under the Chevalier Drucour, a brave and capable commander, who had been much harassed by the difficulties of his position since the war began. There were also some armed inhabitants and a band of useless Indians. But in the harbour lay twelve men-of-war with crews amounting to another 3,000. The fortress was strong enough in itself ; but it was commanded by a hillock only half a mile away inland, while the fleet in the harbour was at the mercy of any batteries that could be erected on the surrounding heights. The British landing was a fine bit of work, chiefly due to Wolfe, who, though the junior brigadier present, was the dominant hero of the siege. Amherst had 12,000 men, twice Drucour's total effectives, while Boscawen's forty-one men-of-war had four times the force of the French squadron in the harbour. The result was a foregone conclusion. The walls were breached; the French ships destroyed. The British united service was making its first great effort under Pitt's own control, and making it well. Not that the fighting was heavy, as the loss on both sides together amounted to only five per cent of the totals engaged afloat and ashore. But the taking of Louisbourg was of the first importance to clear the way to Quebec, to turn the tide of war in America, and to re-establish lost prestige in the eyes of the colonies and the world at large. Drucour's only hope was to hold out long enough to save Quebec from attack; and he attained it, by not surrendering until July 26, though the British expedition had appeared at the beginning of June.

The next month another British success occurred, when Bradstreet, without losing one man, took Fort Frontenac (now Kingston ) and all its stores, with the whole of the nine French vessels on Lake Ontario. At the end of the year the indefatigable Brigadier John Forbes, so ill that he had to be carried on a litter, marched into the famous Fort Duquesne, which the French had abandoned and blown up, and dated his dispatch from 'Pittsbourgh.'

Thus 1758 closed in the deepest gloom for French Canada, which had now shrunk back into a line of little half-starved settlements along the St Lawrence, with outposts on Lake Champlain, and one great natural stronghold at Quebec.

Return to the Seven Years' War home page Source: William WOOD, "The Fight for Oversea Empire: Pitt's Great Administration", in Adam SHORTT and Arthur Doughty, eds., Canada and Its Provinces, Vol. I, Toronto, Glasgow, Brook & Company, 1914, 312p., pp. 260-268. |

© 2005

Claude Bélanger, Marianopolis College |

|

The

central period is the justification of the whole war, and the glory

of the central period is Pitt. He roused the English people to the highest

patriotism. He touched the Celts and oversea British as they never had

been touched from London before, nor have been since. He understood,

as no one in politics before him had, what a British commonwealth of

empire ought to be. He knew how to exert amphibious force in every direction

and combination where it would be most effective. He knew all the relations

between the civil and military resources of the peoples he led to victory,

all the importance of sea-power, all the functions of the British army,

all the strength of a real united service. And-his crowning virtue as

a minister of war-he knew and practised the supreme art of controlling

operations everywhere without interfering with them anywhere.

The

central period is the justification of the whole war, and the glory

of the central period is Pitt. He roused the English people to the highest

patriotism. He touched the Celts and oversea British as they never had

been touched from London before, nor have been since. He understood,

as no one in politics before him had, what a British commonwealth of

empire ought to be. He knew how to exert amphibious force in every direction

and combination where it would be most effective. He knew all the relations

between the civil and military resources of the peoples he led to victory,

all the importance of sea-power, all the functions of the British army,

all the strength of a real united service. And-his crowning virtue as

a minister of war-he knew and practised the supreme art of controlling

operations everywhere without interfering with them anywhere.