|

|

| Date Published: |

L’Encyclopédie de l’histoire du Québec / The Quebec History Encyclopedia

The Fight for Oversea EmpireThe Seven Years War1757 : the Year of William Henry

[This text was written by William WOOD and was published in 1914. For the precise citation, see the end of the document.]

THE CAMPAIGN IN EUROPETHE European campaign of the year 1757 did not open auspiciously for the British side. Frederick won at Prague, but lost at Kolin, and had to evacuate Bohemia. The Duke of Cumberland, at the head of the most considerable British force that had appeared in European war since the time of Marlborough, was defeated at Hastenbeck and rounded up at Closter-Seven, where he signed a convention neutralizing his whole army for the rest of the war. A joint naval and military expedition sent to destroy the French stronghold at Rochefort - a westcoast harbour of great importance between the European and American fields of operation - ended with less disaster but equal disgrace. Hawke was the admiral, and, as his whole career proves, was quite capable of doing his part well. But the three incompetent generals could not make up their minds to do anything at all. After gravely deliberating for five days, in presence of their enemy, over what was intended to have been a surprise, they decided that, as he must have had ample time for preparation, it would be better to let him alone ! However, the fate of Byng may have spurred them to at least a show of action ; for, after another two days, they ordered an immediate landing in full force. After watching their men sitting idle in the boats for three hours, their hearts again misgave them, and they sailed home with the infamy of a complete fiasco clinging round their names for ever. The one redeeming feature was that a young staff-officer of thirty, Colonel Wolfe, took in the situation at a glance, quite understood how the army should have co-operated with the fleet, and attracted the favourable attention of the great Pitt by the marked ability with which he gave his evidence at the subsequent court-martial.

LOUDOUN'S TACTICS

Meanwhile, Loudoun had been busy thinking out a counterstroke to Montcalm's capture of Oswego. His plan was to take Louisbourg early enough to go on to Quebec and finish the campaign there. Pitt was in office for the winter months - much to the disgust of the common run of politicians - and the plan was approved. The money was voted, and in March the city of Cork was alive with the men of the joint expedition being made ready to sail against Louisbourg. Loudoun, on his part, held conferences with all the colonial governors, and, uninspiring as he was, found a good deal of popular support for a scheme which would wipe out the memory of the hated retrocession nine years before. But there was a political crisis in England. Pitt was dismissed for over-efficiency in April ; and during eleven weeks of disastrous war there was no imperial ministry. Admiral Holborne's fleet was still at Cork ; and of course all the information concerning it had been reported to headquarters in France, whence strong squadrons were immediately sent out to Louisbourg. Even Loudoun was getting anxious to make another preparatory move when he and Admiral Hardy had rendezvoused at New York with all the troops and ships at their disposal. But there was no news of Holborne. However, for once, Loudoun took a risk and ventured from New York to Halifax, where Holborne came in a few days later. It was now July ; and Loudoun had, twelve thousand men, more than half of them well-drilled regulars. An attack on Quebec was given up for the time being, and Louisbourg became the sole objective. The new plan was that Holborne should go well ahead, tempt the French fleet out of Louisbourg, and crush it while Loudoun was landing. But in August the French were found to be so strong that all idea of a joint attack was abandoned. Holborne sailed to offer action, which the French refused, and was caught in a storm that did him as much damage as a battle. Thus the seaboard campaign; of 1757 ended in nothing but excursions and alarms.

MONTCALM AND THE INDIANS

Inland the French had early begun trying to confirm their previous successes in the west by driving in the British centre at Fort William Henry. The very night after the Irishmen in garrison had been celebrating St Patrick's Day with toasts in New England rum, Vaudreuil's brother, Rigaud, appeared with 1600 men. There were only 350 effectives in the fort ; but they were ready, and fired so briskly that Rigaud retired, after various futile demonstrations. He left an enormous blaze behind him, in which several hundred boats were burnt. Vaudreuil, in sending this expedition under his brother, instead of a stronger force, under Lévis, or Bourlamaque, as Montcalm had advised, made the double mistake of showing his hand to the enemy by losing the first trick.

At the opening of navigation Vaudreuil received a warning that Holborne was sailing from Cork against Louisbourg and, perhaps, Quebec. Should there be any fear for Quebec all available forces were to be concentrated there. If not, they could be employed offensively, as Louisbourg would be reinforced from France. It soon became evident that Loudoun would never get near Quebec, and so Vaudreuil, in his interfering way, gave Montcalm as little of a free hand as he could to take the field.

That spring there had been an Indian gathering at Montreal the like of which no man had ever seen before. French agents had been active all the winter in the West, where the fame of Montcalm had spread far and wide. The medicine men saw visions of countless British scalps, many of the tribes saw a chance of vengeance against the settlers who had been dispossessing them ; and all expected presents from the French and booty from the British. By the end of June Montreal was swarming with braves from Acadia to the Lakes, the Mississippi and beyond. Here, in one throng, were these wildest of wild savages rubbing shoulders with dames and dandies from the most polished court in Europe. Montcalm, of course, was the one man they wished to admire - the great war-chief who had swept the British from a war-path that now stretched unbroken for five moons' journey, from the Eastern ocean to the Southern sea. They were at first disappointed to find him of only middle height. 'We thought his head would be lost in the clouds.' But when he spoke war to them they recognized him as every inch a soldier. 'Now we see in your eyes the strength of the oak and the swoop of the eagle.'

SURRENDER OF THE FORT

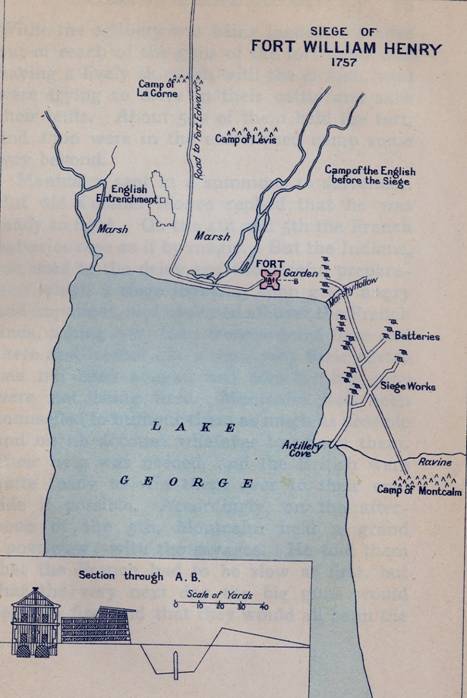

Early in July Montcalm left for the frontier, where Bourlamaque with two battalions had been strengthening Ticonderoga and watching the British since May. The total French force was nearly 8,000, of which barely 3,000 were regulars, including 500 colonials, another 3,000 were militia, and 2,000 were Indians. The British force within supporting distance was about half this. There were 500 men in Fort William Henry under Lieutenant-Colonel Monro, 1,700 in the entrenched camp near by, and 1,600 with the inert Webb fourteen miles away at Fort Edward. The first brush was disastrous to the 300 men of a British reconnoitring party, who were ambushed by Langlade's Indians and Canadians far down the lake. Only two boats escaped out of twenty-three. Several barrels of rum were taken with the prisoners, who suffered death by torture in consequence. Another and much smaller party was surprised near the French camp on August 2 ; several were killed, and three were captured and brought to Montcalm. From them Montcalm found out that Monro had only 500 men in Fort William Henry.

The next morning the French, having brought most of their siege material by water, but a good deal by land over terribly difficult country, pressed round to the investment. The British who were encamped outside had a skirmish with Lévis on their way in, and at the end of it La Corne held the road to Fort Edward with several hundred Indians. Montcalm reconnoitred, saw the fort was too strong to be stormed, and sent in a summons, to which Monro replied that he was ready to defend himself. He expected Webb's 1,600 to come to his relief, and Webb expected reinforcements from the south. Webb was in a critical position. As the Canadians and Indians could not be kept together for any length of time in August, and as he was exposed to defeat in detail with his troops in three parts, he might have blown up Fort William Henry, destroyed the road, and concentrated his 3,800 round Fort Edward. But he sat still ; and on the night of the 4th sent a messenger with a letter to Monro, telling him not to expect help, but to make the best terms possible.

The next morning Montcalm's guns opened fire and sent the splinters flying round the ears of the garrison, to the unbounded delight of the Indians, who yelled like fiends. The British replied energetically, and seemed well able to hold their own. But Webb's messenger was killed on his way in, and Webb's letter brought to Montcalm, who sent it on to Monro with his compliments. However, Monro still held out, though the odds were increasing against him. His best guns were put out of action, while the French batteries were being strengthened. On the 9th he offered to surrender if Montcalm would grant the honours of war. The Indian chiefs were called into council at the French camp, the terms clearly explained to them, and their promise taken that they would prevent any excess on the part of their followers. This was Montcalm's first campaign with any large mixed force of the wilder tribes of Indians ; and he and his lieutenants thought all reasonable precautions that would not unduly offend the Indians had been taken. An escort of French regulars was told off for the following day ; and the British evacuated the fort and concentrated in their entrenched camp ready for an early start.

MASSACRE BY THE INDIANS

But that night some of the Indians got into the fort through the embrasures, in spite of the French guard, and massacred the sick. Montcalm immediately rushed down with an armed party, stopped the Indians, and got two chiefs from every tribe to be ready to march off with the prisoners and escort in the morning. He also sent La Come among them to keep them in hand. The British had an uneasy night and were astir by dawn. Seventeen wounded were tomahawked on the outskirts of the camp before the escort arrived. When the column moved off the Indians crowded in, snatching booty and demanding rum. This, unfortunately, had not been destroyed ; the prisoners furthest from the escort were afraid to refuse; the Indians, who had smelt blood already that day, got wild with drink, and a scene of horror immediately began. Montcalm, Lévis, Bourlamaque and other French officers came running down at the news, and fearlessly exposed their lives in stopping the massacre. Altogether, about a hundred were killed, including those in the fort the night before and the wounded in the early morning. Four hundred, whom the Indians carried off, were rescued and sent into Fort Edward under guard. Others who had fled also got in, guided by cannon fired at intervals. Others again were subsequently ransomed by the French and sent home. The greater number arrived safe at Fort Edward under their original escort.

This massacre naturally excited a fury of resentment among the British ; and many a case of 'No Quarter' was traceable to its memory. It caused the British authorities to cancel the parole requiring the prisoners not to serve again during the war. Some of its victims were avenged by the deadly ravages of the smallpox caught by the Indians in the fort and spread broadcast among their tribes. The facts, of course, were greatly exaggerated by the British ; but they were bad enough. It is quite clear that Montcalm and his officers had no hand in instigating what they risked their lives to stop. Montcalm also has the good defence that he had never before had such wild tribes under him, that there had been no gross outrage at Oswego, that he had taken what seemed to him sufficient precautions, and that his duty compelled him to court the Indians, while his position denied him a really effective command. At the worst, he made an error of judgment, for which he was unduly blamed. (1) The Canadians, accustomed to border war, ought to have known better; but many of them ostentatiously disregarded the possibility of an outrage, and some of their wilder spirits egged the Indians on. As for the Indians, they had exactly the manners and customs of the prehistoric age in which the French and British would themselves have acted just as savagely.

(1) A close study of that unhappy incident justifies entirely, in our mind, Montcalm's conduct on that occasion. He did his best to ensure the safety of the English prisoners. (Note of the special editor.) Return to the Seven Years' War home page Source: William WOOD, "The Fight for Oversea Empire: Fort William Henry", in Adam SHORTT and Arthur G. DOUGHTY, eds., Canada and Its Provinces, Vol. I, Toronto, Glasgow, Brook & Company, 1914, 312p., pp. 254-260. |

© 2005

Claude Bélanger, Marianopolis College |

|