|

|

| Date Published: |

L’Encyclopédie de l’histoire du Québec / The Quebec History EncyclopediaThe Fight for Oversea EmpireThe Seven Years WarThe Declaration of War (1756)[This text was written by William WOOD and was published in 1914. For the precise citation, see the end of the document.] THE COMBATANTS

The formal declarations of the motherlands against each other were fine specimens of the mutual recrimination common on such occasions, and showed the prevailing national attitudes to a nicety. The French pose before what they conceived to be the attitude of civilized Europe was well matched by the stolid self-righteousness of England.

The two powers differed so profoundly in the nature and application of their armed forces that a general comparison is almost impossible. In area, population and natural resources France greatly surpassed England, and, indeed, the British Isles. Its army was more than twice as strong, all things considered. But in government, the navy and external trade the British were easily first. Not that the British government of 1756 was a good one, not that it was by any means free from corruption, and not that its successor in 1763 was any better; but that the French were decidedly worse. Their previous reign had seen at least one generation of military glory under an absolute king. The succeeding reign was to end in a revolution which, with all its evils, was to produce a marvellous development of warlike strength. But in the long interval between the 'Roi Soleil ' and Napoleon the faculty of national leadership was numbed by corruption and perverted by misgovernment. In naval power England, as usual, had been losing ground during peace, while France, also as usual, had been recovering it. Still, the British fleet could put about one hundred ships into the line, at fairly short notice, against about forty-five on the side of the French. Roughly, it may be said that as the French army was twice as strong as the British would ultimately make theirs, so the British navy was at least twice as strong as was the French at the start. The other great powers who took part - Prussia, Austria and Russia - did nothing to alter the balance at sea. Spain, which had a fleet, was both too weak and too late to be of real use. In the mercantile branch of sea-power the British were very much more pre-eminent. All the staying power was on their side. Every one of their naval victories made the sea safer for their own trade and more dangerous for the enemy's ; until theirs reached a height of prosperity it had never attained in time of peace, while the enemy's withered away to almost nothing. What made the difference all the more decisive was that every increase of British sea-trade increased the national resources convertible to warlike ends, and of course correspondingly decreased those of the French. This was nowhere more felt than in Canada, where money, supplies, reinforcements, trade, and even presents for the Indians, all failed at their source when cut off from the sea.

THE FRENCH POSITION

The French position in Canada was, therefore, a weak one in a general way, as the line of communication with the base passed over a hostile sea. Yet it had several elements of local strength, which, if turned to better account, might have staved off the conquest long enough to give France another opportunity of holding her own in America by European diplomacy. The country was a natural stronghold, except for its easy access from the sea. But even the St. Lawrence was quite defensible. The land lines of invasion were all much more so. The direct approach to Quebec by the Chaudière river was exceedingly difficult, especially for a large force. The line of Lake Champlain offered many opportunities of water transport from New York to the St Lawrence. But the portages and several other places, if fortified, could be held against greatly superior numbers.

And though a land of waterways might be supposed to offer the general advantage to the British, this was not then the case in Canada ; for the French were in possession of the whole line of the St Lawrence and the Great Lakes, except at Oswego, which they soon captured. In canoe and bateau work on inland waters they had nothing to learn from their rivals. Thus the country was particularly strong against any inland invasion, which of course could only be effected along a few definite lines, and not through the immense wilds, which practically barred the way to considerable armies.

The French forces in Canada were generally fitted for their task. The militia was composed of all the able-bodied men in the colony. These men could rough it, march and shoot; but they were not well disciplined or drilled, and were of little use at close quarters in the open. Including old men and quite young boys they never mustered twenty thousand, and nothing like this number could take or keep the field in a body, as that would bring all the civil work of the country to a standstill. Even in smaller numbers they could not be kept long under arms in seeding-time or harvest. The troupes de la marine were companies of colonial regulars under the administration of the department of Marine. But they were soldiers pure and simple. They came mostly from and sympathized with the militia, and, like them, were trained for bush-fighting. They never numbered much over two thousand effectives and were rarely formed in any higher unit than the company. The backbone of all the forces was the troupes de la terre or regulars from France. The officers, as a class, were not professionally equal to the Prussians - neither were the British. But, taken for all in all, the French regulars in Canada would bear comparison with any others of their day; and they upheld the best traditions of their most military nation. Seamen as combatants were oftener employed ashore than afloat: there never was any naval battle worth the name in Canada. The numbers varied, but probably never exceeded fifteen hundred at any one time, exclusive of those at Louisbourg. The last force was the Indians, most of whom, except the Iroquois, took the French side. They were, in every sense of the word, a fluctuating quantity. Altogether, it is safe to say that the very utmost strength which could ever be mobilized could not exceed 25,000 men, grey-beards and boys, all told. Of these, not 5,000 at the outside would be French regulars, 2,000 Colonial regulars, 1,000 seamen, 14,000 militia and 3,000 Indians. And it is doubtful if all the real effectives ever exceeded 20,000 in the whole theatre of operations.

MONTCALM AND VAUDREUIL

But

these 20,000 were led by Montcalm,

in every way a splendid leader and by far the greatest Frenchman in

the whole New World. He was of illustrious birth. His family for centuries

had been so famous in the field that there was a well-known saying,

'La Guerre est le tombeau des Montcalm.' [War is the grave

of the Moncalms] He had remarkable aptitude for the intellectual life

as well as for soldiering, and might have aspired to a seat in the French

Academy as well as to a marshal's bâton. He was born in 1712,

succeeded

Vaudreuil, the governor-general, was anything but pleased to see Montcalm. These two men were utterly incompatible. Vaudreuil was a vain and fussy pettifogger, who had

constantly reported home against having any French general sent out, in order that he might have no expert check on his own ridiculous leadership. Unfortunately, he had the right of supreme command whenever he chose to exercise it. And he alone could command all the five different kinds of forces - French regulars, colonial regulars, seamen, militia and Indians. He could delegate his authority; but he never gave with one hand without taking away with the other. His character developed as the war went on, and always for the worse. The best that can be said of him is that he was more fool than knave. But Bigot, the intendant and head of the civil administration, was all knave. His character, too, grew worse and worse as time went on.

Even at first Montcalm realized his unfortunate position. Technically, he only commanded the French regulars. The seamen were under their own officers; the rest more directly under Vaudreuil, who was. also commander-in-chief. Yet Vaudreuil, Bigot and Montcalm could all report direct to France : Thus there were five distinct forces under three different heads. It was the autocratic system without the autocrat on the spot. Moreover, transport, and even the horsing of guns, was done by civil contract, and, of course, always badly and dishonestly done by Bigot's underlings.

However, things went fairly well at first. There was work ready and waiting; and, for once, all the authorities agreed that the taking of Oswego was the best way to open the regular war. Four battalions of troupes de la terre had come out in 1755. Two more arrived in 1756, and two more yet in 1757. Their names have become famous in the history of war - Guienne, Béarn, Languedoc, La Reine, La Sarre, Royal-Roussillon, and two battalions of Berry. The average effective strength of each was only about 500, making 4,000 in all. The artillery from France was never very numerous, and there was no cavalry. One great advantage was that the men all embarked in high good humour. The Canadian campaigns attracted the French army even more than they had ninety years before when the Carignan-Salières went out with de Tracy, fresh from their victories over the Turks.

BRITISH PREPARATIONS

Meanwhile preparations for war were going on among the British in America. Shirley, an energetic man but not a general, was first appointed, and then superseded as commander-in-chief by Lord Loudoun, who happened to be a general but certainly was not an energetic man. Under Loudoun were Abercromby and Webb. Loudoun never did anything decided, Webb as little as he could, and Abercromby invariably made mistakes. Shirley's plan was the comprehensive one of taking Fort Duquesne and the French posts along Lake Ontario, surprising Ticonderoga early in the year by an expedition across the ice, and threatening Quebec itself from the line of the Chaudière. But Shirley had to hand over the command to Webb, who handed it over to Abercromby, who handed it over to Loudoun. Loudoun forwarded the preparations as much as he could. Seven thousand New York and New England levies, under Winslow, gathered and advanced against Ticonderoga in the summer; but they never got further than the line of British forts. At the end of June Abercromby arrived at Albany, where Shirley urged him to strengthen Oswego. But he kept his men busy digging trenches at Albany instead. At the end of July Loudoun also arrived, upset Shirley's plans altogether, and issued an order that no provincial officer should rank higher than a captain in the regulars. Even Loudoun saw the unwisdom of putting men who had shown a certain ability as generals - like Johnson, Lyman and Winslow - under some possibly muddle-headed major who had never seen active service. But mere politicians were ordering such things at home, and the Great Statesman was not yet wielding the forces of the Empire. No wonder Pitt was writing 'I dread to hear from America '!

While the British colonies were as disunited and cantankerous as usual, the British home government even more than usually obtuse, and Loudoun marking time with twelve thousand men, the French were up and doing. In March Vaudreuil sent an expedition which destroyed Fort Bull, a post on the line between Albany and Oswego. In May he sent Coulon de Villiers, Washington's victorious opponent at Fort Necessity, to intercept the British supplies for Oswego. This raid was partly successful. But Bradstreet, an excellent colonial officer, had a successful brush with some of the raiders and learnt the French plans and strength from a couple of prisoners. He at once reported to Loudoun, who thought over it for a month, and then sent Webb forward when it was too late.

THE CAPTURE OF OSWEGO

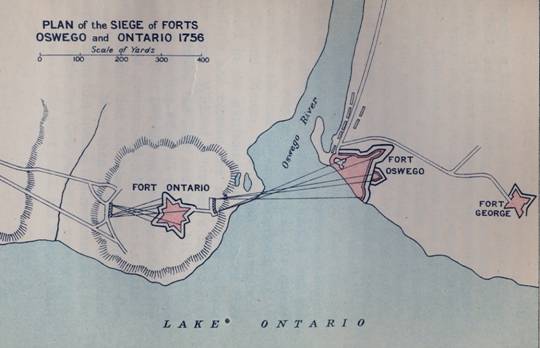

Montcalm had picked up the threads of his complicated work in May. In June he had hastened to the defence of Ticonderoga, where he had left a garrison to safeguard it against Winslow. In July he was preparing his counterstroke against Oswego. New to the country, its ways and men, he was at first inclined to doubt his ability to take the fort with the means at his disposal. On July 20 he wrote to the minister of war in France saying that he could not make sure that the details were being properly combined before he had to leave Montreal for Frontenac. On his way up he stopped to parley with the Iroquois chiefs at La Présentation, from which place he sent them back to Vaudreuil, who kept them under surveillance, as no one knew which side they would take. On the 29th he was at Frontenac, where his men were cheered by the news of de Villiers' raid at the beginning of the month. His advanced guard had already landed at Niaouaré Bay, now Sackett's Harbour, which was the appointed rendezvous of his whole force of 3,000 men, half regulars, half militia, with 250 Indians. On August 8 all were concentrated there, and he marched to surprise Oswego, moving by night, and hiding his men and material by day. Towards midnight on the 10th he arrived within striking distance, began a battery on his right, and camped between it and a protecting marsh on his left. There were three forts at the mouth of the Oswego, one on the right bank, Fort Ontario, one opposite on the left, Fort Oswego, and a third half a mile further on, Fort George. The garrisons numbered 1,700 men. Fort Ontario was untenable against siege artillery, its twelve guns were soon put out of action, and its garrison crossed over to Fort Oswego, on which Montcalm immediately concentrated his attack. Fort George was small and weak and of no use to either side. The 1,700 provincials - partly more or less seasoned men, partly raw recruits - had a good fort, thirty-three guns, and a capable leader, Colonel Mercer. But Mercer was no match for Montcalm, who opened his batteries across the river at 450 yards, and sent his Canadians and Indians over and round to attack in rear. Mercer was killed, the garrison became demoralized, and there was no news of Webb's reinforcements. On the 14th the British capitulated, and surrendered 1,600 men, 121 guns, plenty of ammunition, and the 6 armed vessels and 200 other craft prepared for Shirley's proposed expedition against Niagara and Frontenac.

The capture of Oswego was the most consummate feat of arms in living memory among the colonials and Indians. Its strategical significance was evident to all. It secured the inland line to Louisiana, with both sides of all the great waterways. When Montcalm destroyed the fortifications he gained the goodwill of the local tribes as surely as he had impressed them by his victory. They naturally argued that while the British had come to alter their way of life; the French would let it take its own course again by leaving them alone.

A YEAR OF BRITISH DISASTER

Thus the opening year of the war ended badly for the British cause in every respect. Colonel Armstrong found three hundred fighting-men in Pennsylvania to follow him in a successful raid on the Delawares between Venango and Fort Duquesne. But the French Indians who took the warpath all along the frontier did far more damage in return. There had never been a better season for what some grim wags called 'hairdressing.' It is said that an Indian who had killed the French engineer at Oswego by mistake actually made amends by lifting no less than thirty-three British scalps within the succeeding twelvemonth.

There was no better news for the British from the East than from the West - this was the year of the Black Hole of Calcutta. And at the centre of world-power the prospect seemed equally bad. Frederick the Great had overrun Saxony and beaten the Austrians. But armies were gathering against him, in one long enveloping crescent, from Paris to St Petersburg. Hanover was in imminent danger, to the great distress of George II, and the double alarm of the cabinet, the weaker members of which wanted to hire Hanoverians for the defence of England against a French invasion. And France, with an eye to a future Spanish alliance, had taken Minorca, from which the governor and thirty-five officers, in a garrison of three thousand men, were absent on leave. Worst of all, a British fleet under Byng failed to retrieve the situation. This stung England to the quick. Byng was shot - the mediocre victim of a mediocre system and a mediocre ministry - and a 'cargo of courage,' under Hawke and Saunders, was sent out to replace him. Strangely enough, the French admiral, La Galissonière, was an ex-administrator of New France, Saunders commanded the British fleet in Wolfe's campaign at Quebec, and Hawke's clinching victory in Quiberon Bay sealed the fate of New France. In view of the complete triumph of the British arms three years later, the despondency and panic in 1756 seem almost incredible. But they were very real ; and men's hearts failed them when they felt the ship of state in the grip of the storm without any trusted pilot at the helm. Return to the Seven Years' War home page Source: William WOOD, The Fight for Oversea Empire: The Declaration of War", in Adam SHORTT and Arthur G. DOUGHTY, eds, Canada and Its Provinces, Vol. I, Toronto, Glasgow, Brook & Company, 1914, 312p., pp. 246-254.

|

© 2005

Claude Bélanger, Marianopolis College |

|

to

the marquisate in 1735, and the next year married Angélique Talon

du Boulay, a blood relation of the famous Jean Talon, intendant of New

France, in 1665. His military career had been a most distinguished one.

Ensign at fifteen, he fought at Kehl and Philipsbourg in the Polish

campaign. In 1741 he was aide-de-camp to the Marquis de la Fare in Bohemia,

where he won the cross of St Louis. Colonel in 1743, he twice rallied

his regiment in the French defeat at Piacenza in 1746, received five

wounds and was taken prisoner. After six years of peace, mostly spent

at his beloved family seat of Candiac with his wife and children, he

accepted the Canadian command, after it had been pressed upon him twice,

set out for Paris, studying Charlevoix' History of New France, had

audience of the king, promptly settled his military affairs, sailed

from Brest in the Licorne, had a stormy passage of thirty-eight

days, landed at St Joachim, and drove the remaining twenty-five miles

to Quebec in a calèche, arriving on May 13.

to

the marquisate in 1735, and the next year married Angélique Talon

du Boulay, a blood relation of the famous Jean Talon, intendant of New

France, in 1665. His military career had been a most distinguished one.

Ensign at fifteen, he fought at Kehl and Philipsbourg in the Polish

campaign. In 1741 he was aide-de-camp to the Marquis de la Fare in Bohemia,

where he won the cross of St Louis. Colonel in 1743, he twice rallied

his regiment in the French defeat at Piacenza in 1746, received five

wounds and was taken prisoner. After six years of peace, mostly spent

at his beloved family seat of Candiac with his wife and children, he

accepted the Canadian command, after it had been pressed upon him twice,

set out for Paris, studying Charlevoix' History of New France, had

audience of the king, promptly settled his military affairs, sailed

from Brest in the Licorne, had a stormy passage of thirty-eight

days, landed at St Joachim, and drove the remaining twenty-five miles

to Quebec in a calèche, arriving on May 13.