|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Date Published: |

L’Encyclopédie de l’histoire du Québec / The Quebec History Encyclopedia

The Indians of Western Canada

[This text was written by Rev. George Bryce and was published in 1898. For the full citation, see the end of the document. The sections on religion and "recent Indian history" particularly show their age. Rev. Bryce is unable to show enough detachment or objectivity. To him, Natives were easy prey to "superstition", being led by medicine men, "cunning as a fox", and who held "infamous power". These rendered the work of Christian teachers "ineffectual". The section on Treaties readily shows the intellectual context for the policy of assimilation that was carried out by the Canadian government in the late XIXth and XXth centuries. The reader should also note that Eskimos are more appropriately known as Inuit today. Despite their defects, these sections have been reproduced for their historiographical value.]

THE Algonquin nation. - On the 14th of June, 1671 , the French explorers met at Sault Ste. Marie a great concourse of Indians. While these were not all of one race yet the fact that Father Allouez addessed them in Algonquin shows that the Algonquin influence was a prevalent one upon the north shore of our Canadian lakes. This "pageant of St. Lusson," as it has been called, was a marked event in the spread of French influence among the northern tribes.

In 1701, after the French and Indians had wearied themselves in destructive wars, a great gathering of tribes, from even a wider area than that which the spectacle of St. Lusson had witnessed, took place at Montreal . Amid salvos of artillery and discharges of small arms the peace of North America was declared. Here were assembled, we are told, Abenaquis, Iroquois Hurons, Ottawas, Miamis, Algonquins, Pottawatamies, Outagamis, Saulteaux, and Illinois. This list, while it tended to represent all our northern Indians, includes others as well, though a proper classification will show that many of them were Algonquins.

On the rocky shore of the Atlantic the strong, heavy-boned, and sturdy Algonquins were first met by English colonists and French explorers. They extended west of the Alleghanies, northward to the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and westward again to the Laurentide country, even to the far west prairies. Known by various names along the Atlantic seaboard, these branches of the Algonquin nation have almost all passed away. A few of the same people remained in the Micmacs and Melicetes [Malecites] of Nova Scotia, and in the Abenaquis, who wander along the shore of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Coming westward the most hardy branch of the Algonquins is found in the Ojibiways or Chippewas, who live along the north shore of the St. Lawrence, and Lakes Nipissing, Huron, and Superior. To the Ojibiways seemed to have belonged the Ottawas, who dwelt on the river bearing their name, but moved west to Manitoulin Island and the west shore of Lake Huron. The Ojibiways, clinging to their country of wood and rock, have been a widely scattered but self-relying people. Dwelling in their round-topped, birchbark wigwams, at home on their lakes and streams in their bark canoes, and living on fish and game, they have held their own as a powerful race, and have again and again been successful in driving back, the fierce Iroquois and the bloody Sioux.

Modified by climate and surroundings the Ojibiway branch of the Algonquins became a separate people, called the Crees, or in early books Christineaux or Klistinos. They speak a dialect of the same language, and are in physical aspect similar to the Ojibiways. A later emigration to the west seems to have taken place among the Ojibiways from the neighbourhood of Sault Ste. Marie. A century and a half ago they were called Saulteaux, and are spoken of at Nepigon, on Lake Superior, as the most numerous tribe of the locality, as being wanderers - "not planting anything, and subsisting solely by the chase and fishing." Saulteaux are found at the present day as far west as Lake Winnipeg. The Crees are a more adroit and adaptable people than the Ojibiways. Beginning at Lake Winnipeg they stretch to Hudson's Bay. On account of this region being one of swamps, or muskegs, they are known as the Crees of the Muskegs, or Muskegons. They have proved much more tractable than the Ojibiways, have largely adopted Christianity, and received education fairly well. Shades of difference in dialect may be detected every hundred miles or so on the way from Lake Winnipeg to Hudson 's Bay. Going westward from Lake Winnipeg up the Saskatchewan the Wood Crees are found, who being now similar in circumstances to their Ojibiway ancestors resemble them more in character. As the prairies south of the great Saskatchewan are reached what are known as the Plain Crees are met. These wanderers, leaving behind their canoes as they deserted the rivers for the horses on the plains, and giving up their birch bark wigwams for the leather teepees of the plains, are said to number not less than sixteen thousand souls. Near the source of the south branch of the Saskatchewan live a large nation, some seven thousand in number, known as the Blackfoot nation. These, though differing in some respects from the Crees, have yet resemblances to them in language, and in the present state of our knowledge may be included with the Crees as being of Algonquin origin.

(2) Dakotas or Sioux . - As the early French explorers passed through the Upper Lakes , they met a new nation of Indians coming from Lake Superior . They were known as the "people of the lake," and were so like the Five Nation Indians in appearance, that the French called them "the Little Iroquois of the West." Like the Iroquois, they were a nation of allies, and from this bore the name Dakotas , but they have always been best known as the Sioux. Their language is somewhat like that of the Iroquois, and their lithe figures, aquiline noses, and intellectual features mark them as handsome Indians. It has been surmised that the Iroquois and the Sioux are but different branches of a war-like people, who, coming up the Mississippi on their line of conquest, divided at the mouth of the Ohio River, the one part going to the north east, the other part northward to the "land of the Dakotas," to the west of the great lakes. So fierce are they in disposition and cruel in war that the Sioux have been called the "tigers of the plains." Along the southern boundaries of our Western prairies of Manitoba and Assiniboia is the old territory of the Dakotas . In 1861, the great Sioux massacres of Minnesota took place, and this led to the flight of Sioux refugees to the north side of the boundary line. Several settlements of the Sioux are thus found in Manitoba. They are good farmers, and are, to a considerable extent Christianized.

Strangely like the history of the Iroquois has been that of the Sioux. Years before the coming of the white man a feud arose in the most northern tribe of the Dakotas; and it was so severe that a portion broke off from the nation altogether and became deadly enemies. These took up their abode on the Assiniboine , the largest tributary of the Red River , which runs entirely through Canadian soil. This tribe became known as the "Sioux on the Stoney River," as the name Assiniboine means in Cree. This people have always been friendly with the Crees; know their language and have largely intermarried with them. Scattered bands of Assiniboines are found in Assiniboia, and even west to the Rocky Mountains . On the Souris River a remarkable outlier of brown sandstone rock rises on the prairies. This was called by the early French explorers "Roches Percées," and the name still remains. It was a famous rendez-vous for Crees, Assiniboines, and even Sioux. Their picture-writing may still be seen upon it, commemorating their history. To them it was the abode of the Manitou. And here the nations all assembled, laying aside for the time their feuds and being at peace with one another. Here were re-produced the scenes of peace so pleasantly related in " Hiawatha" in connection with the red pipestone quarry, a locality to the south east of "Roches Percées."

(3) The Chippewayans or Athabascans. - To the north of the country of the Crees is met a very different Indian people known as Tinné or Chippewayans. They are not to be mistaken for the Chippewas, as they dwell far north near Fort Churchill on Hudson 's Bay, and extend west to Athabasca and Slave Lakes. They even live along the Peace River, and are still found as that river is ascended to the west side of the Rocky Mountains. A tribe called the Sarcees, alongside the Blackfoot nation on the boundary line near the Rocky Mountains, are relatives of the Chippewayans. Other tribes of this Athabascan people, as it is called, are found even as far south as New Mexico. The Athabascans, sober in habits, are timid in disposition, are great travellers, and are peculiar in not having the intensely black hair nor the piercing eye of the other Indians.

(4) Indians of British Columbia . - There is a great admixture of races on the Pacific Coast. This gives colour to the supposition that it was from the Indian Archipelago, from the Aleutian Isles, and even from different points on the eastern coast of Asia that our Indian peoples originally migrated. One of the best known tribes in British Columbia is the Haidas, of Queen Charlotte Islands , who also occupy the adjoining mainland. On the coast islands the Haidas exceed six thousand in number, and their villages with grotesque totem poles carved in the forms of birds or various animals, showing the crest of the clan, are well known. In the neighbourhood of Fort Simpson are the Tsimsiahs, a branch of the Haidas. The Nutka Indians inhabit the islands of Vancouver, and have many tribal subdivisions. To the Selish, or Flatheads, of the Columbia mainland belong many tribes of the Lower Fraser River , and also the Shushwaps, far up the mountains, on the Columbia and Okanagan rivers. A tribe, formerly powerful on the Columbia River, near its mouth, the Chinooks, is now almost extinct. Its language, intermixed with English and French words after the coming of the traders, became the trade language of the Pacific Coast under the name of the Chinook jargon. Almost all the coast tribes were familiar with it. A physical difference marks the mountaineers of British Columbia from the coast Indians, for while the latter, who live on fish, are dwarfed and lacking in spirit, the inland tribes are noted for their independence and athletic skill.

(5) The Eskimos. - Far away to the north, beyond the Arctic circle, live the Eskimos, or, as they call themselves, Innuits [Inuit]. They are found on the Labrador coast, on Coppermine River , on the shore of the Arctic Sea , and on the Alaskan Peninsula . Along with the Chippewayans to the south, they number, on Canadian soil, twenty-six thousand souls. The Eskimos are not, as many think, a race of dwarfs, though their stoutness has led to this opinion. Dressed in sealskin clothing and dwelling in huts of snow, these people of the north find their way from place to place in sledges. These are drawn by wolf-like dogs, which have taken their name from their masters of "Espies," or "Huskies." Over the open fjords the Eskimo sailor in the short summer shoots in his "kayak," or one-seated skin boat ; or carries his family in his "umiak," or flat-bottomed boat, so well known to all readers of the accounts of Arctic exploration. The seal and walrus on the coast and the reindeer on land supply food to the Eskimos. Skilful in the manufacture of implements, these ingenious savages, from walrus tusk and whalebone, make harpoons, spears, spoons, ladles, ornaments, and trinkets of every kind. The Eskimos are a peace-loving, tractable, and clever, though somewhat gross, people.

Archaeology. - In the region to the west of Lake Superior many mounds are pointed out which speak of an ancient race. They are built of earth, but sometimes contain layers of stones and even constructions of timber. They are generally circular in shape, and are from six to fifty feet high, and from thirty to one hundred feet in diameter. Usually situated on cliffs or points of advantage along the lakes or watercourses, they undoubtedly served the purpose of observation or defence. In addition they seem to have been used as the cemeteries of the race that built them. They usually contain skeletons, some of them in a sitting posture ; others have collections of skulls, while in some the bones have mostly turned to dust. Along with the bones are found implements and trinkets which were buried with the dead. Stone scrapers and gouges, axes and malls are abundant; lumps of red ochre, pieces of bright shining pyrites, ornamental shells, beads, and wampum are frequent; while numerous tubes of soapstone occur which are believed to have been used by the medicine men in their incantations. On Isle Royale, in Lake Superior , traces are found of a former working of the native copper seams of the island ; and many hundred miles west of the lake the mounds are found to contain copper drills, hooks of copper, and even copper circlets for the head. All of these are of native copper, and no doubt came from Lake Superior .

Most interesting of the remains in the mounds are the cups or fragments of pottery. These are of all shapes and sizes, and are ornamented with markings of every variety. The question has been raised whether or not these mounds contain the bones of the ancestors of the present Indians. The fact that the mounds are usually found in fertile districts points to their builders having been agriculturists, and the frequent occurrence of pottery shows them to have been somewhat civilized. These features distinguish them from the present Indians, who are neither agricultural nor industrial in their tendencies. Our Indians maintain that these are not the bones of their ancestors, but that they belonged to the "Keteanishinate," or very ancient men. Probably the best suggestion made is that they were of the Taltecan race, which formerly inhabited Central America, who were agriculturists, and pottery makers, and who spread over different parts of America during the 7th and 12th centuries. These seem to have been swept away by the eruption from the south represented by the Iroquois and Sioux migrations, and this fiery flood of extermination may have been about the time when the white man first appeared in the American interior. At that time, three centuries ago, they saw the remnants of the Hochelagans, Eries, and Neutrals being swept away in savage fury. The secret of the Alleghans, as the vanished race has been called, will probably never be unearthed. Most of the Indian tribes have a tradition of the deluge, and amongst the Western Canadian Indians there is a pious legend of a great deliverer who came to clear the rivers and forests and fishing grounds, and to teach peace and its arts. This myth circles around Lake Superior, and was collected by Schoolcraft, who was for many years Indian agent at Sault Ste. Marie. It is but the heart of man crying out for higher help, and the expectation handed down that a deliverer would surely, come. This Algonquin myth is found among the Micmacs of Nova Scotia in the story of their deliverer, the doughty "Gluscap."

Language. - The Indian languages, while differing very much, have a general feature of resemblance, in that they are all "incorporating languages," i.e., have the feature of building up words by agglutination, or of putting all parts of speech together in one great compound. Words of great length are thus constructed, and this is a more marked feature of our Indian languages than even of the Basque of the Pyrenees - the old world representative of this type. The Algonquin languages have been very persistent in form, though having many dialects. Being entirely spoken languages, some difference in form has been made according as the linguist who reduced them to writing was French or English. The different spelling of many of the Indian names is thus accounted for, as example, Owinipigue (French), Winnipeg (English); Kris or Christmeaux (French), Crees (English). The different dialects, especially of Cree, require much study to master their peculiarities. Tribes such as the Crees and Assiniboines, that mixed much together, generally used the language of the stronger. Accordingly many of the Assiniboines understood Cree. Among the Indians of British Columbia no less than eleven well-defined dialects have been made out. The sign language is extensively used among tribes of different speech, and it is marvellous to what extent two solitary horsemen meeting each other on the plains, and unable to address a single word to each other, can interchange ideas. Picture writing was also much practised among the Indians, and maps of large districts are made with considerable skill. It was a map drawn by a very unlettered Indian which was followed by La Vérendrye on his exploratory voyage from Lake Superior to the interior of the Winnipeg country.

Indian Dress. - Before the coming of the white man, the red men chiefly depended for their dress upon the skins of animals taken in the chase. They early discovered the art of tanning the skins of wild beasts, and their women are still able from these to make a soft and supple leather. Garments, often highly ornamented, made from this leather, enabled them to defy the cold in their northern home, which they called Keewatin - the land of the north wind. From this leather was also made the moccasin, shod with which the Indian could steal through the forest as noiselessly as a panther. For crossing the snowy fields, either of forest or prairie, the snow-shoes, a broad frame covered with a network of leather thongs, were used with great skill. The hunter on his snow-shoes easily captured the deer or buffalo caught floundering in the heavy snow. In their dress the Indians have always shown the greatest love of ornament. The braves decked their heads with the feathers of the hawk and eagle, while both men and women wore ear-rings, bracelets, strings of beads, ornaments of bone and shell, and smeared their faces with red and yellow ochre. The Indians of to-day, though in many places settled and dressed more after the manner of the whites, yet here and there still show traces of these customs of their fathers.

Amusements. - The different Indian tribes have a remarkable similarity in their customs and habits of life. Living largely by hunting and fishing they are accustomed to have much time on their hands. This leads them to seek for company, and accordingly on the plains large camps were found among the Indians in their wild state. The Indian dearly loves the social gathering and the pow-wow. The assemblages of the old men were characterized by great conferences, in which Indian eloquence reached its height in interminable speeches. In the evenings a great variety of dances were indulged in (see Catlin's North American Indians ), and the neighbourhood of a camp of heathen Indians is still notable by the incessant sound of the "tom-toms," or small drums, beaten by the squaws as an accompaniment to the dance. The Indians of the plains likewise have many athletic games in which they take great delight, and have an inveterate fondness for horse-racing. Perhaps the greatest evil in the large camps is the fondness for gambling found among the young and old. Gamblers have been known to sit through the whole night, and men have gambled away every possession belonging to them, including the last horse and even the wife best beloved. The feasts found among the Indians of the woods were also practised by the Indians of the plains, and were always scenes of the greatest revelry, and frequently ended in violence.

Religion. - [Consult the introduction for comments on the following section.] Among the western Indians their religious rites often ran with their feasts and amusements ; indeed, many of their feasts were based on religious sanctions. With high imaginative power, the mind of the Indian went readily towards superstition. Whilst believing in a great spirit, the "Gitche Manitou," yet his actions seemed more frequently dictated by fear of the spirit of evil, or "Matche Manitou." All Indians have an unbounded confidence in magic, or, as they call it, "bad medicine." The conjuror, or medicine man, is an adept in the use of this terrible agent. Acquainted with the medicinal powers of the herbs of the field, using his knowledge as a terrifying agent, ingenious in his use of natural phenomena, and cunning as a fox in his estimate of motive and character, the medicine man could make peace or war, destroy the influence of the chief, or render ineffectual the work of the Christian teacher. The great religious rite of the plains was the "sun dance," conducted under the direction of the medicine man. This was the introduction of the young braves into the established position of warriors. Assembled together, the multitude looked upon the candidate for elevation. Young men submitted to piercing the muscles of the chest, and tying thongs through the openings, which were fastened to ropes. By this, though suffering intense agony, the stoical youth was lifted, and frequently persisted till he fainted away.

The system of superstition was thoroughly organized, and had great influence among the western tribes. Along with this there was some worshipping of the Manitou, and some of the tribes worshipped the rising sun. All the Indians believed in a future state, and that a different place awaits the good man from that to which the bad is sent. In burying their dead the Algonquins usually chose a beautiful spot in the forest, or the headland overlooking a lake or river. The Sioux and other western tribes sometimes exposed their dead on platforms or on the branches of trees. Freed from the infamous power of the magician, the Indian belief had much in it to make a dignified, brave, honourable, though somewhat taciturn manhood.

Recent Indian History . - In looking back for more than a quarter century since 1871, the writer has seen many changes among the Indians of the west. It is true that at the beginning of that period many of the Indians were far from being entirely savage. The Indians of St. Peter's, for example, on the Red River , seemed nearly as far advanced as they are to-day. For fifty or a hundred years the Indians of this district have been under the influence of Europeans. Much of their intercourse with the whites was hurtful, yet the Hudson's Bay Company, with a wise self-interest, if from no higher motive, treated the Indian well; did not allow him to go very deep in his use of the firewater - the bane of his race - and gave him credit for such supplies in advance as he needed, a trust very rarely abused. The Hudson 's Bay Company Indian, indeed, almost formed a distinct type of Red man. He was an easygoing, light-hearted mortal, shrewd in trade, agile on foot or in canoe, fond of his ease, and taking on very much the character of his immediate superiors, good or bad, as they chanced to be. In 1871 all the tribes were in a ferment. The old order had passed away. What was the new to be ?

The Indians were restless. All remember the exorbitant demands, the long debates, the Indian fickleness and sulky grumbling, that the Commissioners met with when in Governor Archibald's time at Lower Fort Garry and Manitoba Post, Treaties One and Two were made, and when Governor Morris negotiated at Northwest Angle Treaty Three. The Indians were unwilling to allow even the surveyors to sub-divide the land, and the joint expedition of 1872, which on behalf of Great Britain and the United States surveyed the 49th parallel, was threatened. For several years after the occupation of the North-West by Canada, the movements of the other Western Indians, as well as the Sioux, were so uncertain that frequent despatches of an anxious character were forwarded to Ottawa by the Governor of Manitoba. On the 4th of March, 1873, an urgent petition to the Governor was forwarded by Rev. John McNabb, Presbyterian minister at Palestine (now Gladstone ), then the farthest point of settlement. The anxious pastor with 55 others complained of the threatening attitude of the Indians and of the defenceless state of the settlers, and asked for arms and ammunition.

In 1872 the Sioux at Portage la Prairie were so domineering that the settlers dared not refuse their demands, and were in constant fear. The reports - often canards - of murder and theft on the plains were of weekly occurrence in Winnipeg in those days. The Indian question was regarded as a most difficult one by our statesmen. We were told that Canadians had never dealt with large bodies of Indians; that Blackfeet, Bloods, and Sarcees, and even the Plain Crees, were bent on mischief; that they would hold the plains against us, mounted as they were on fleet steeds and armed with repeating rifles, obtained from the American traders. The Little Saskatchewan, and Fort Ellice, and Turtle Mountain were out of the world in those days; Prince Albert and Edmonton were the "Ultima Thule"; while Forts "Whoop-up " and "Slide-out," in the Bow River country, were the inaccessible haunts of horse thieves and desperadoes. How changed now! Our Government boldly and successfully met the threatened danger. They made treaty after treaty. It was seen that not only must the Indian be quieted, but also that steps should be taken for his improvement. The wandering habits of the Indian render his subsistence precarious. If possible therefore he should be induced to settle down upon a reserve. There he may have a house ; after that agriculture and cattle raising might be possible for him. Naturally averse to labour, he must be induced and pressed to become more and more self-reliant. He must be educated, and at any rate his children trained to a civilized life.

The following are the treaties which have been made with the Indians and interesting facts connected with them:

All these treaties promised certain reserves to the Indians. In most cases these were selected after the Treaty by the joint action of the Government agent and the bands themselves. The reserves were given on the basis of 640 acres for each Indian family of five. All the lands of the reserve, however, belong to the band.

Once upon the reserves the chief of the tribe, elected by the Indians themselves, but who must have the approval of the Government, has a sort of rule or precedence. Each agency is divided up into a number of districts, and over each district an agent is appointed who must be a resident of the district, and whose duty it is to give his sole time and thought to the advancement and comfort of the Indian. When Treaties One and Two were made they were not so favourable as those afterwards agreed on. One and Two were revised, and now it may be said the terms of all the treaties are virtually the same. The following are the leading features:

At Treaty, $12 to each male member of band. Annually thereafter, $5 each. Annually, each head chief, $25 ; three subordinate chiefs, $15 each. $1,500 worth of ammunition and twine annually to the band. For each band, one yoke of oxen, one bull, four cows. Seed grain for all the land broken up. One plough for 10 families. Other agricultural and mechanical implements and tools. There was to be a school on each reserve. No intoxicating liquor to be sold on the reserve. Right to fish and hunt on unoccupied land of the district.

Among the most cheering things in the negotiations of all the treaties was the earnest desire of the Indians for the education of their children. In Treaty Three this is embodied in the following words: "Her Majesty agrees to maintain schools for instruction in such reserves hereby made as to Her Government of Her Dominion of Canada may seem advisable, whenever the Indians of the reserve may desire it." I am glad to be able to state from the best authority that the Indians not only desire schools on their reserves, but are clamourous for them. Of course there will be difficulty in maintaining the regular attendance of the children, but this is a thing not unknown among whites. While not among the illusionists, who regard the Red man in his savage state as a hero of the Fenimore Cooper type, yet I know from many years' hearsay and experience that in intellectual ability the Indian is much above the average of savage races. He has a good eye; he learns to write easily; has a remarkably good memory as a rule, and while not particularly strong as a reasoner, he will succeed in the study of languages and the pursuit of the sciences. Of course the school begun on an Indian Reserve must be, in most cases, of the most primitive kind, particularly until the wandering habit is overcome.

As illustrating the native aptness of the Indians one has but to examine their "picture writing." This is so ingenious that an Indian chief will keep the whole account of his dealings, and that of his tribe with the Government, with absolute exactness. Take for example the transactions of Mawintopeness, chief of the Rainy River Indians. On a single page not larger than a sheet of foolscap are the transactions of several years. This system, which is one of very simple entry, does not occupy one-tenth of the space filled in the Government records of the same affairs. Governor Morris, tall and slender, is recognizable with a gift in his hand; each year has a mark known to the writer ; the chief recording the fact that he has recieved each year $5 bounty and $25 salary, is represented by an open palm, a piece of money, and three upright crosses, each meaning $10; his flag and medal are represented; his oxen and cattle are recognizable at least, and so on with his plough, harrow, saws, augurs, etc. The same chief, noted for his craft, represents himself between the trader and the teacher, looking in each direction, showing the need of having an eye on both. Interesting examples of Indian bark letters, petitions, etc., of a pictorial kind, may be found in Sir John Lubbock's Origin of Civilization . Many specimens can be shown of paintings in colours, done by an Indian artist, and though not likely to be mistaken for those of Rubens or Turner, yet they are interesting.

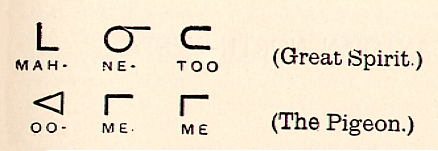

Another most interesting feature of Indian intelligence is the widespread use among them of the syllabic character - of which the following is an example:

This is a system of characters invented about 1840 by Rev. James Evans, at the time a Methodist Indian missionary to Hudson's Bay. Since that date it has spread - especially among the Crees - even far up the Saskatchewan . It is used extensively by the Indians in communicating with one another on birch-bark letters. It may be learned by an intelligent Indian in an afternoon or two, being vastly simpler than our character. The British and Foreign Bible Society, the Church of England and Roman Catholics use this syllabic character in printing Indian books. When Lord Dufferin was in the Northwest he heard of the character for the first time, and remarked that some men had been buried in Westminster Abbey for doing less than the inventor of the syllabic had done, and during the visit of the British Association in 1886, a number of the most distinguished members expressed themselves as surprised at an invention of which they had not previously heard.

Back to the Indians of Canada and Quebec page Source : Rev. George BRYCE, "The Indians of Western Canada ", in Canada. An Encyclopaedia of the country, Vol. 1, Toronto, The Linscott Publishing Company, 1898, 540p., pp. 220-227. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

© 2005

Claude Bélanger, Marianopolis College |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||