|

|

| Date Published: |

L’Encyclopédie de l’histoire du Québec / The Quebec History Encyclopedia

Economic History of Canada

[This text was written in 1948. For the full citation, see the end of the document] The economic history of Canada until 1850 was dominated by waterways. The fur-trade pressed westward by the St. Lawrence with its tributaries and the Great lakes; the fishing industry, the fur-trade, and the lumbering industry depended upon water transport. Only since 1850 have wheat-raising, mining, and pulp and paper become important. industries dependent upon rail transport.

It was as a fishing ground that Canada was first approached by Europeans. The enormously productive waters of the coasts and later of the Banks were visited by French and Portuguese in the first half of the sixteenth century. English fishermen, lacking solar salt, of which large supplies were needed for the green fishery practised by other Europeans, developed the dry fishery, and established themselves securely on the Avalon peninsula of Newfoundland in the second half of the century; their fishery expanded as prices rose in Spain following imports of treasure from the New World and the collapse of the Spanish fishery. French participation in the dry fishery necessitated penetration to the more distant regions of Canso and Gaspé, and the fur-trade had its beginning when these fishermen met Indians of the St. Lawrence and its tributaries.

The French Period .

After the discovery by the French of a vast supply of furs, the spread of the fashion for beaver hats, and the demands of the Indians for iron and gunpowder, the fur-trade pushed up the valley of the St. Lawrence, where there was freedom from attack by other European countries and safety for monopoly control. The great forested Precambrian shield gave an abundance of beaver skins which were brought down by the rivers - first the Saguenay, and later the St. Maurice and the Ottawa - to the French traders in exchange for European goods. Successive monopolies were obliged to meet the serious inroads of the Iroquois from the south supported by the Dutch on the Hudson . With the practical extermination of the Hurons by the Iroquois, the fur-trade for the moment almost ceased.

Under these conditions, monopolies failed, and settlement made little progress. In 1663, under the aggressive interest of Colbert, Louis XIV revoked the charter of the Company of New France, and governed the colony from the throne. The Carignan-Salières Regiment not only subdued the Iroquois, but furnished settlers for lands along the Richelieu. Immigrants were sent out in numbers, and seigniories were liberally granted. The church and the seigniors prescribed a feudal pattern for the life of the habitants, and the fur-trade drew men to the woods, so that agriculture, handicapped by climate and difficulties of clearing, progressed slowly. Wheat crops were small and uncertain; few cattle were kept; and the colony was closely dependent upon France for goods, and even for food.

With increase in population, French traders were compelled to penetrate the interior and re-establish the trade route to the west destroyed by the Iroquois. Forts were built along the Great Lakes at Frontenac [ Kingston ] and Niagara to check the Iroquois from the south. The granting of a charter to the Hudson 's Bay Company in 1670 opened English competition from the north as well, and led to successful naval attacks by the French until they were compelled to abandon Hudson Bay in 1713. Success in military measures brought its problems in rapid increase in production of furs, decline in price, and eventually in the issue of card money and inflation.

In the maritime region, the fishing areas of Canso and Gaspé were separated from the fertile agricultural areas of the basin of the bay of Fundy. The exposed character of settlement made it an easy prey to the English, and necessitated withdrawal from Nova Scotia under the Treaty of Utrecht. The French attempted to consolidate the new position by fortification of Louisbourg at Cape Breton . New France could not support itself, and the fishery resorted to illicit trade with the dyked lands of Acadia for cattle and with New York and Philadelphia for flour. Conflict between the New England and French fisheries led to the capture of Louisbourg, establishment of the English at Halifax (1749), and expulsion of the Acadians from the fertile lands of the bay of Fundy [1755-1762].

After the Treaty of Utrecht, the English had the advantage of supplies of cheap West India rum and access to Oswego on lake Ontario on the south, and of cheap ocean transportation to Hudson Bay on the north, so that the French were forced to push westward by Kaministikwia over a new route opened by La Vérendrye to lake Winnipeg and the Saskatchewan. The new area yielded an abundance of furs; but the distance from Montreal increased transportation costs, and the additional expense of the war brought the fur-trade and the colony to collapse and the victory of the English.

The Early British Period .

After the expulsion of the Acadians and the Treaty of Paris, New England colonists entered Nova Scotia and extended the fishery to Cape Breton , the gulf of St. Lawrence, and Labrador . Jersey islanders established fishing stations at Gaspé and Cape Breton. Expansion of the New England fishery and New England trade in the Maritimes and of the fur trade of New York in the interior involved increasing conflict with the restrictive measures of the Navigation Acts and of legislation such as the Sugar Act in the interests of the British West Indies . Canada had been added to the Empire rather than Guadeloupe in order not to increase the production of British West Indies products and to increase the consumption. Conflict in the Maritimes and in the interior, with the inevitable conflict between the St. Lawrence and the Hudson, hastened the outbreak of hostilities after the Quebec Act, which attempted to restrain internal development in much the same fashion as the French had done prior to 1763. Collapse of the British Empire followed that of the French.

After the Treaty of Versailles in 1783, a great influx of Loyalists poured into Nova Scotia and New Brunswick . Free lands and supplies were provided, but agriculture remained of less importance than the fishery in Nova Scotia and lumber in New Brunswick . Fish and lumber were sent to the West Indies , but both suffered from American competition. The Napoleonic wars were followed by a heavy preference on lumber from British North America and expansion of the industry on the rivers of New Brunswick . The War of 1812 closed the British West Indies to American ships, with the result that Nova Scotia became a more important base for exports and re-exports of fish and other products. The Convention of 1818 [The Rush-Bagot Treaty] followed the War of 1812, and served as an effective base in restricting the New England fishery in British waters.

The shift from French to British allegiance brought to Canada the markets of the British Empire and a rapid development of trade and industry. New roads were built and post-offices established; new crops and improved methods of agriculture were introduced. Seigniories were taken over by English officers and soldiers were settled on the lands. Shipping increased; and flour, potash, and staves became important articles of export.

In 1783 and after, Loyalists came in to occupy the lake and river shores of Upper Canada . The soil was fertile, but hard to clear, and when surplus crops could be produced there were no roads over which they might be carried and no markets to receive them. By 1798 over a million acres had been granted in Upper Canada ; and wheat, brought down by water, began to be an important export crop. Labour was scarce, and industry was confined to the small local grist mill, tannery, bootmaker and carriage shop. The retail trade of the country was carried on by country merchants who received wheat, potash, and other products for export in exchange for imported manufactured goods. Heavy imports received at Montreal and Quebec went to Upper Canada , to the Indian country, and to the American west, which found the St. Lawrence the cheapest outlet to the sea.

On the St. Lawrence the bateau and Durham boat appeared to supplement the canoe, and these were followed by the lake schooner and the steamer. The first steam vessel arrived at Quebec in 1809, and in 1816 the first steamship was launched on lake Ontario . Yonge Street and Dundas Street were built to serve the interior; and stages ran between Montreal and Kingston and in the long-settled Niagara district, but roads continued to be severely needed and postal services were correspondingly slow.

As in New Brunswick , lumbering began in the Ottawa valley at the beginning of the century under the stimulus of imperial preferences, and white pine, floated down to Quebec , became the chief export of the country. In 1818 three hundred thousand tons of shipping, nearly all carrying square timber, left British North America for Great Britain . Duties on foreign timber were lowered in 1820, and the timber trade suffered temporarily from overstocking of the market.

In the fur-trade, English manufactured goods and trading capacity were combined with French experience. The English fur-traders had rum and woollen cloth; the French had a body of men who knew the river routes and how to deal with the Indians. Traders from Albany moved to Montreal and penetrated to the west, their ventures leading, with the heavy .costs accompanying penetration to the Saskatchewan and Athabaska and the outbreak of the American Revolution, to the formation of the North West Company. Canoes following the old Ottawa route were supported by lake boats which carried heavy goods to Grand Portage to be distributed by lighter canoes to the Saskatchewan, the Churchill, and the Peace rivers. The Hudson 's Bay Company met this new competition by sending men westward to persuade Indians to come to Hudson Bay, and by establishing new posts, beginning with Cumberland House in 1774.

Closing of the Albany-New York route with the outbreak of the American Revolution, narrowing of British trade after the Treaty of Versailles, withdrawal of the traders from the western posts under the Jay Treaty, and the aggressiveness of the North West Company led to expansion of the fur-trade to the Mackenzie and the Pacific coast drainage basin. The extended system of canoe routes and forts and limitations of territory brought violent rivalry with the Hudson 's Bay Company. A trade in which monopoly had always been important found intense competition to be fatally destructive. The Selkirk settlement as a means of strengthening the Hudson 's Bay Company brought open warfare. The inevitable amalgamation was achieved in 1821 when the partnership system, the experience, and aggressiveness of the North West Company were combined with the charter rights and the strategic situation for cheap water transport of the Hudson 's Bay Company.

Fishing, shipping, and trade continued to be the principal activities of Nova Scotia. The bay of Fundy became important as diversified fishing increased, and the gulf of St. Lawrence and Chaleur Bay yielded large quantities of cod. The West Indies were the market for fish, particularly until 1830, when the United States was admitted to the West Indies trade, and until 1833, when slavery was abolished; and lumber, coal, fish, and potatoes were sent to the United States.

The timber-trade continued under a substantial preference until it was forced to adjust itself to new and apparently harsh conditions of free competition, followed by reduction in the early forties. While timber interests raised the cry of ruin, it was obvious that Canadian white pine, with its durability, freedom from imperfections, and great length, could hold its own against Baltic timber without the assistance of duties; and the slumps from which the Canadian timber trade suffered were due not to removal of the preference, but to the usual violent fluctuations in the timber trade and its dependence on constructional activity. Moreover, forests of the eastern United States were disappearing while population increased, and a new and promising market opened there for Canadian timber.

The effects of the timber trade on New Brunswick and the Canadas were evident in rapid expansion of settlement. New Brunswick received large numbers of poor immigrants, though there was a slow drain of emigration, both from that province and from Nova Scotia . St. John alone had 450 vessels in the timber trade in 1840. Ship-building became important, for timber was abundant, labour cheap, and the enterprise profitable, but the vessels came to be hastily and badly built. After the collapse of 1825, better ships were built in fewer numbers.

Upper Canada was the goal for immigrants who came in great numbers in the thirties and forties. Dilapidated timber vessels carrying emigrants instead of ballast brought enormous numbers, under conditions of severe hardship, subject to epidemics and to the risks of a long and dangerous passage. Paupers were sent out by parish aid; naval and military officers and pensioners were given land grants; but the bulk of immigration was unassisted. From immigrant ships the terrible cholera epidemics of 1832 and 1834 spread up the country, and the opposition of Lower Canada to an influx entirely English-speaking was intensified by the penniless and diseased condition of the multitudes who crowded the port of Quebec . Newcomers were welcomed in Upper Canada until the arrival in 1847 of a great army of starving Irish, victims of the potato famine. Thereafter restrictions were imposed, and the health of immigrants improved. Over a third of a million immigrants entered Canada in the decade of the forties alone.

Immigration and settlement raised problems of land distribution. The size of land grants was reduced, and after 1815 the grants were generally about one hundred acres. In 1826 a system of land sales was introduced. Settlers on wild land met with difficulties from Crown and Clergy reserves and from speculation, by which large blocks of land were withheld from cultivation. For settlers possessing some capital, the Canada Company in western Ontario provided lots served by roads and accessible to mills and towns. The British American Land Company performed the same service in the Eastern Townships, which were later occupied by French settlers from the older settled parts of Quebec.

Cultivation was poor, livestock suffered severely, and wheat lands were ruthlessly cropped without crop rotation or fertilization; but the rich, virgin soil of Upper Canada yielded freely, and settlers soon had surplus crops ready for market. But they were separated from a market by miles of forest intersected by miserable roads blocked by reserves, and by waterways interrupted by dangerous rapids, necessitating numerous trans-shipments. The Erie canal had been opened from Buffalo in 1825, and canals were demanded to carry wheat from Upper Canada to the ocean ports. The Welland canal was opened in 1830, the Rideau in 1831, and others followed. Successful competition with the Erie route was, however, prevented by the obstruction of the upper St. Lawrence. Upper Canada intensely desired an outlet, but had little capital, while Lower Canada with control over customs from the important port of Montreal and opposition from the Assembly hindered improvements. The canal scheme could not be carried out until the Act of Union in 1840 provided adequate financial support and focussed the energies of both provinces on the task. Steamships were able to descend to Montreal from lake Ontario by 1850, and the channel across lake St. Peter was steadily deepened after that date.

Exports of wheat and flour were hampered not only by the expense and delay of the long, laborious journey to England, but also by reduction of the preference given in the Corn Laws. Free entry of Canadian flour to England was permitted in 1843, and mills were rapidly built, only to be ruined by the abolition of the Corn Laws in 1846. But completion of the St. Lawrence canals in 1849 and construction of railways in the fifties reduced the difficulties of transport, and the wheat and flour trade expanded rapidly.

Trade continued to be restricted to British ships by the operation of the Navigation Laws, though inland waters such as the St. Lawrence and the Great lakes were exempted. Along the great stretch of open border, there was much smuggling of tea and silk from the United States, and of sugar and broadcloth from Canada. The Trade Acts of 1822 and 1825 were followed by abolition of the Navigation Laws in 1849.

Industry developed as a result of the expense of importing British goods. The St. Maurice Iron Works at Three Rivers had produced small quantities of iron for more than a century and, with the Marmora Iron Works, made stoves and axes. Agricultural implements were nearly all imported. Tanning, distilling, and brewing were widely distributed; West India rum was supplanted by whiskey made from cheap supplies of grain. There were a few paper, glass, and woollen mills; but none of the products were of high quality or sufficient to supply the needs of the country. Capital and technical skill were lacking, while the demand was limited, for towns were small and farms self-sufficing.

The fur-trade shifted from the St. Lawrence to Hudson Bay after 1821; and the vast western territory was developed under control of the Hudson's Bay Company. York boats carried to the interior from the posts on Hudson Bay goods brought by vessels from England, and collected furs to be carried back to London. In the interests of economy, farming was introduced at the posts, and extended at Red River settlement. Independent traders harassed the Company by setting up competition in out-of-the-way places, and the resistance of Red River settlers to the Company's control raised the first flurries of the storm to come. On the Pacific coast, the Hudson's Bay Company was forced to retreat from the Columbia to Victoria and the Fraser by the movement of population in the United States to Oregon and the loss of that territory in 1846.

Shipbuilding, lumbering, and fishing continued as the basis of the economic life of the Maritime provinces; and their decline after 1850 with the introduction of the railway and steamship created serious difficulties. Wooden shipbuilding was destroyed, and sailing ships were forced into local or remote trade lanes. Steamship and railway traffic built Halifax and St. John into dominant ports at the expense of the outports. Telegraph and cable lines added to coastal steamship services, and local railway lines brought the two cities into the realm of world trade, while roads were extended into the back country. Financial problems which accompanied building of railways and the decline of wooden shipbuilding contributed to Confederation and construction of the Intercolonial Railway. The completion of the latter in 1876 connected Canada and the Maritimes, and gave Canada means of access through Canadian territory to Great Britain during the closed season of the St. Lawrence. Square timber, the staple of New Brunswick, was becoming scarce, and saw mills multiplied, turning out spruce deals and lumber for export. From Nova Scotia, as well, deals were sent to Great Britain, the United States, and the West Indies. Cod continued to dominate the fishery, but the trade in other varieties of fish was extended. The Reciprocity Treaty from 1854 to 1866 and the Washington Treaty from 1885 widened the markets. In Gaspé and the Canadian Labrador the industry continued to be controlled by large firms which exported to the Mediterranean and South America.

The days of the wood and water economy which had prevailed from the earliest times in a country possessing one of the greatest of rivers and one of the widest of forests, had given way to a new economy of coal and iron. The monopoly of the General Mining Association was broken in 1856, and the Reciprocity Treaty opened in the United States a market for Nova Scotia coal. The Cape Breton mines sent coal to Montreal by the Intercolonial and the St. Lawrence ship channel, and further deepening of the waterways stimulated sales to steamships calling for bunker coal and coal for the upper provinces.

With the dominance of fishing, lumbering, and mining, little attention was given to agriculture. Farming, as in the Ottawa valley, was subsidiary to lumbering, providing horses, hay, and oats. Wheat brought over the railways from Upper Canada weakened the unstable position of wheat production; but root crops were grown, and the rich dyked and intervale lands of the bay of Fundy continued to support large herds of cattle, as they had done for two hundred and fifty years. In Prince Edward Island potatoes became important for export.

The Age of Steam and Iron.

The coming of an age of steam and iron brought serious changes to the St. Lawrence basin. Canals had been provided by 1850, but they were already outdated by competing railway lines in the United States, and iron ships were needed to carry goods abroad when railways had brought them to the ports. Timber ships, particularly, old and over-loaded, were often lost, and the early years of ocean steamship traffic to the St. Lawrence were strewn with disasters. The discovery of petroleum and its suitability for signal lights hastened the building of lighthouses, and cable and telegraph systems and meteorological services made navigation less hazardous.

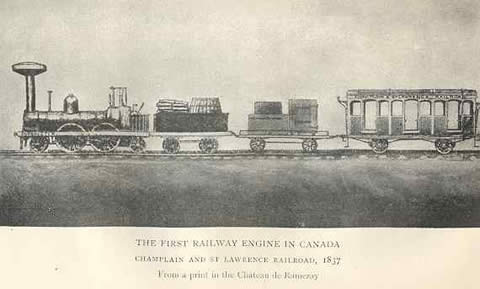

Steamships grew rapidly in size so that the deepened waterways were soon too shallow, and the canals and the ship channel had to be deepened again and again. The complicated St. Lawrence route, with its canals of varying depth, its heavy towage and pilotage fees, and high insurance rates, fell steadily behind in the traffic race with the Erie canal and the American railways, which furnished an easy route to New York with low insurance rates and a large available tonnage. The Welland Railway was built to solve the problem presented by the shallowness of the canal, but the delay and trouble of transshipment prevented a large increase in traffic. Waterways could no longer compete with New York trunk railways, and in 1856 the Grand Trunk was completed from Toronto to Montreal. Many branch lines were constructed to lake ports and to towns in the interior to build up both through and local traffic. In 1860 sixteen railway companies operated 1,800 miles in Canada, using iron rails, burning wood, and owning 384 locomotives. In 1875 thirty-seven railways operated 5,157 miles laid with iron or steel rails, and owned 1,000 locomotives.

Railways had a profound influence on the timber trade, which was forced to give way to more developed industries serving the needs of a developing community. Exhaustion of more accessible large trees for square timber was followed by exploitation of smaller trees in the sawn-lumber industry. Saw-mills and wood-working plants appeared at convenient water-power sites on the Ottawa, and as railways offered transportation facilities, steam mills were built in the interior to serve areas not served by water. Embargo on export of logs cut on Crown lands in Ontario (1898) was followed by the establishment of mills on the north shore of Georgian Bay.

The waning square-timber trade and the lumber industry based on white pine were followed by exploitation of spruce on the large tributaries of the St. Lawrence and in turn by the pulp industry. Pulpwood was exported to mills in the United States, and ground-wood mills followed by paper mills flourished in areas where spruce was abundant, rail and water transport available, and the American market near. Provincial embargoes in Ontario and Quebec on pulpwood cut on Crown lands hastened the migration of paper mills, particularly to the St. Maurice and the Ottawa, and improved methods of transmitting hydro-electric power encouraged concentration of the industry. But wood was no longer the great staple product of the country, for the farms settled in the thirties and forties had not only trenched on the forest, but were producing great quantities of wheat for export. In 1863 it was said that half the vessels which formerly took on cargoes of lumber at Quebec now went to Montreal for grain.

The prosperity of the country had rested first on the fishery, and then on the Precambrian shield for its yield of fur, and later for its rafts of square timber. A growing population had pushed back the margins of the forest to the hostile edge of the rock, and waterways which had sufficed for fish, fur, and square timber had become, even with laborious improvement, too slow and dangerous for the use of steamships and the carriage of perishable products. Railways opened new land to settlement, and carried wheat raised on older lands to the seaboard for export. By 1860 the best lands were occupied, so that colonization roads had to be built, and special inducements offered to immigrants to take up poorer and less accessible lands.

But intensive wheat-growing brought its own nemesis, for, as in Lower Canada a generation earlier, overcropped and unfertilized lands became worn out, and wheat was gradually replaced by coarse grains and by the raising of livestock. Sheep and oxen, characteristic of the frontier farm, gave way to horses and cattle. The steamship facilitated the shipment of dairy products, particularly cheese in the sixties and livestock in the seventies. The growth of towns opened a market for dairy products, especially butter and milk. Cattle-raising and dairying involved rotation in agriculture and construction of farm buildings; fields had to be fenced, and root and forage crops raised and stored for winter use.

Industry in Canada , with the exception of stave-cutting and flour-milling for export, was almost entirely local and domestic until the demands of the new steam and steel era made themselves felt. The iron industry produced only a few stoves and potash kettles till it was stimulated by the demands of the railways for rails and car wheels. Domestic bog ores were becoming exhausted, and pig iron imported from England and the United States was manufactured in foundries situated along lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence for the sake of cheap coal supplies and easy water transportation. Sewing machines, agricultural machinery, and implements of all kinds were produced; and the Massey and Harris firms were established. Under the protection of the National Policy, industries increased rapidly, such as woollen and knitting mills, boot and shoe factories, and foundries. Hardwood was made into furniture in many Ontario towns, and Montreal became the site of many factories producing hardware, textiles, soap, drugs, paint, rubber goods, tobacco, and paper. Factories sprang up at sources of water-power, and where water-power was limited railways brought cheap supplies of coal.

The apprenticeship system had been superseded by the coming of the factory system, which in turn brought serious evils - child labour, long hours, insanitary and dangerous working conditions, depressed wages. The first trade union in Canada , the Typographical Society, had been formed in York ( Toronto ) in 1832. Co-operation between unions was attempted in the Toronto Trades Assembly, which met in 1873; and the Trades and Labour Congress of Canada was organized in 1886.

With the launching of the first steamboat on the Red river in 1859 a new era began in the prairie region, and the ancient monopoly of the Hudson 's Bay Company came to an end. Trade to the west ceased to come from Hudson Bay , and was carried on from the south. The Company's lands were acquired by Canada , and Manitoba became a province in 1870.

The building of the Canadian Pacific Railway and the peopling of western Canada were hastened by the discovery of gold in British Columbia . On the Pacific coast the gold rush in California in 1848-9 and the migration of prospectors northward led to the discovery of gold on the bars of the Fraser in 1857. Prospectors pushed on from the bars of the Fraser to the Cariboo, where shafts had to be sunk to find the pay streak on bed rock, and operations became expensive with extensive equipment and heavy transportation costs. The fur-trade transport system on the Fraser provided a route for incoming prospectors; steamers were soon adapted to the difficult river navigation; and the Cariboo trail was eventually extended to the interior with stages and pack trains. Gold like a magnet drew a variety of necessary services and products. Food and lumber were hastily imported, and flour mills and breweries were built.

The fishery developed especially after canned salmon was first exported in the early seventies, and lumbering increased rapidly to meet the needs of building and mining. Coastal saw-mills exported lumber to all parts of the world. Coal, mined at Nanaimo since 1852, supported steamship navigation. Costs of roads to the interior and the debt which became more burdensome with exhaustion of the gold fields became important considerations in the union of Vancouver island and British Columbia and in the agreement by which British Columbia joined Confederation in 1871. Construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway carried out one of the terms of the agreement.

Confederation.

Confederation emerged as a solution to the financial problems of the St. Lawrence, the Maritimes, and the Pacific coast, and implied construction of the Intercolonial Railway to the Maritimes and of the Canadian Pacific Railway to the coast. The National Policy of 1878 was designed to encourage east-to-west traffic on the recently completed Intercolonial (1876) and as a part of the support to the Canadian Pacific Railway. Rapid construction of the latter under private enterprise provided a transcontinental railway from Vancouver completed in 1885 and to St. John in 1890, and introduced a transcontinental main line tending to concentrate on Montreal in contrast with the main line of the Grand Trunk which followed the St. Lawrence system from Portland on the Atlantic to Montreal, Toronto, Sarnia, and Chicago. The problem of ceaseless competition of the St. Lawrence with American routes was met temporarily by expansion to western Canada .

Surveyors followed the Free Land Homestead Act of 1872 to the newly acquired territory of the North West , and settlers followed the survey and the railway. Farmers left the exploited lumber regions, and the exhausted wheat lands of the Canadas to settle in the west. Population of Manitoba increased from 25,000 in 1871 to 152,000 in 1891. On the Pacific coast American lines tapped the Kootenay mining region. Silver was discovered at Toad mountain near Nelson in 1886, and a smelter was built. Copper gold in the Rossland district and silver, lead, and zinc properties in the Slocan in the nineties led to construction of the Crowsnest pass line from Lethbridge to Kootenay in 1898. Coal and coke from the Crowsnest mines supplied the smelter at Trail and the smelters which followed extension of the railway to the copper-ore bodies of the Boundary district.

The long succession of gold discoveries on the western coast extending from California in 1849 to the Cassiar in the seventies was crowned by the finding of gold in the Klondike in 1896 and the famous rush of 1898. Transport to the region was exceedingly difficult until a railway was built from Skagway to Whitehorse in 1900, and problems of mining in frozen ground were met by the introduction of machinery and dredge and hydraulic operations. As the scale of operations increased, capital control and consolidation replaced hand labour and individual enterprise.

The demands of the population of mining areas stimulated the production of agricultural products in British Columbia and in Alberta . Increase in population on the Pacific coast and improvement of navigation and transportation widened the domestic and external market for lumbering, particularly in the coastal regions. Similarly, the fishing industry became the basis of an extensive development with construction of canneries on the Fraser and the northern rivers. Specialized agriculture emerged in the production of milk and vegetables in the Fraser valley and of fruit in the irrigated areas of the Okanagan, and with specialization came an important co-operative movement. The spectacular boom of mining development on the Pacific coast in the nineties coincided with the end of a long period of depression. As the gold rush of the fifties and sixties was largely responsible for construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway, so the mining boom of the nineties fostered immigration and settlement.

Immigration to the prairies from the United States increased rapidly at the beginning of the century. As free land disappeared in the United States , British immigration to the Canadian West increased, and immigration from continental Europe became important. The new provinces sprang into being, and villages rapidly became full-fledged cities. By 1913 homestead entries had begun to decline, because more desirable free land had become scarce arid the West was emerging from the early pioneer stage. As a result of problems of marketing and transportation, there arose -important and successful cooperative enterprises in all three provinces, and a vigorous struggle was waged to secure cheaper and more adequate transport facilities.

Demands for lower rates secured the Crowsnest pass rates agreement of 1896 and hastened construction of rival railway lines, the Canadian Northern and the Grand Trunk Pacific. Capital equipment was increased with labour, and by 1914 the Canadian Northern had been extended to Vancouver and the Grand Trunk Pacific to Prince Rupert . Towns, elevators, farm buildings sprang into existence with increase in population and production of wheat. The resources of the prairies were exploited more adequately, and the effects were evident far beyond their boundaries. British Columbia exported lumber and agricultural produce to the prairies, and eastern Canada sent manufactured products, including rails and railway equipment.

Rapid expansion of wheat production, which accompanied cultivation of the prairies and extension of the spring wheat area, with development of Marquis and other varieties of wheat, raised serious problems of transportation from Winnipeg to the seaboard. Fort William and Port Arthur became terminals for grain from western Canada , and lake steamers were developed to handle grain to Buffalo and to Georgian Bay ports for re-shipment to Montreal . Completion of the upper St. Lawrence canals to fourteen feet by the beginning of the century, deepening of the ship channel to twenty-five feet, and improvement of the gulf, with the development of wireless, enabled Montreal to establish a position of first importance as a competitor with New York for North American grain. The National Transcontinental from Winnipeg to Quebec and Moncton was designed to handle grain to Quebec and Maritime ports, but has been unsuccessful.

Expansion of the West became a powerful stimulus to the growth of industry and increase in urban population in the St. Lawrence. Toronto increased from a population of 86,000 in 1881 to 181,000 in 1891, 209,000 in 1901, and 381,000 in 1911; Montreal , from 140,000 in 1881 to 219,000 in 1891, 328,000 in 1901, and 490,000 in 1911. The population of the Dominion increased from 4,833,000 in 1891 to 7,206,000 in 1911, and the percentage of population living in cities and towns increased from 37 in 1901 to 45 in 1911.

Effects on the agricultural implement industry were evident in amalgamation of numerous companies, the expansion of the Massey-Harris Company, and the establishment of branch factories of the International Harvester Company. Blast furnace plants at Hamilton and Sault St. Marie produced steel for agricultural machinery and the railways; but the demand could not be met, and large quantities were imported. Hydro-electric power development centred at Niagara Falls supported rapid expansion of industrial growth. Increasing population in western Canada created demands for eastern manufacturers and provided the raw material for rapid expansion of the flour-milling industry and the growth of livestock industries.

Exports, principally to Great Britain , of livestock and dairy products, fell off early in the century, for supplies of meat, cheese, and butter were needed to feed the industrial population at home. The building of silos, the use of corn for silage, refrigeration, and meat and milk inspection all tended to improve products. In specialized areas, such as the Niagara peninsula, for fruit growing, and the Essex district, for tobacco, canning and other industries emerged. Government experimental stations and agricultural colleges exerted a wide-spread effect on agricultural technique. Rise of the domestic market accompanied expansion of exports from New Zealand and Australia , and as Canada withdrew from the British market her place was taken, as a result of improvements in refrigeration, by the Antipodes .

Industrial expansion in the St. Lawrence was hastened by the development of mining, which accompanied penetration of the Precambrian formation by the railway. Under the wood, wind, and water régime, metals had been little needed, and mining was of slight importance. The more accessible minerals characteristic of later geologic formations, such as oil, salt, and gypsum, had been produced and put to local use. Apatite was mined for export. Asbestos was discovered and mined in quantities near Thetford, Danville , and East Broughton in Quebec . Silver was mined on Silver Islet after 1868 by an American company.

During the construction of the main line of the Canadian Pacific Railway, nickel was discovered at Sudbury in 1883; but the importance of these great nickel-copper deposits was not appreciated until the discovery of improved methods of treating the ores and of the many uses for nickel as an alloy with steel, copper, and other metals. The first smelter was blown in 1889, and production increased so greatly that in 1913 the International Nickel Company and the Mond Nickel Company supplied 69 per cent. of the world's production.

Twenty years after the Sudbury discovery, railway builders found deposits of silver at Cobalt. The rush began in 1904; surface claims were rapidly exhausted; and shaft-mining replaced open quarrying. Mining machinery was followed by hydro-electric power development and in turn by establishment of concentrators. Silver production reached a peak in the Cobalt district in 1911.

Gold was found in Whitney and Tisdale townships in 1909, and in 1911 the railway reached South Porcupine. Capital acquired in older regions supported the new mines. "Porcupine is really the child of Cobalt." Hydroelectric power developed on an extensive scale to meet the heavy demands of the region. The Kirkland lake district followed Porcupine. The mines not only produced important quantities of minerals for export, but helped to bear the cost of the railway system, the construction of which had revealed their existence and contributed to establish manufacturing and diversified agriculture in eastern Canada .

The effects of expansion of western Canada were evident in the St. Lawrence region and in turn in the Maritimes. Montreal demanded increasing quantities of coal and the railways involved demands for rails and cars. A number of the stronger Cape Breton mines were amalgamated in 1893 as the Dominion Coal Company, and provided a base for expansion of the iron and steel industry early in the century at Sydney . Iron works, strategically located near coal mines in the Pictou region, produced pig-iron and supplied the railways with forgings, spikes, and car-axles. The Nova Scotia Steel Company, an amalgamation of several earlier companies, in 1894 acquired the iron ore deposit at Wabana , Newfoundland , and built furnaces at North Sydney to supply rolling plants, car shops, and related industries at New Glasgow. The expansion of railways opened a large demand for rails, cars, and other products, and 90 per cent. of the annual consumption of steel rails in 1914 was supplied in Canada . The iron and steel industry of Nova Scotia , based on deposits of coal and iron ore and convenient water and rail transportation, developed rapidly.

Rise of industrial centres had important effects on other industries. As in the St. Lawrence, agriculture became specialized in relation to urban demands in the expansion of the dairy industry, with emphasis on butter and milk. Competition from the St. Lawrence accentuated specialization. The Annapolis valley grew apples which were sold under a central co-operative agency and largely exported to Great Britain . A highly developed mixed-farming region emerged in Prince Edward Island , which culminated in fox-farming. Potatoes continued to be an important export crop there. In New Brunswick specialization in potato production was in evidence, but lumbering continued an important competitor.

Steamers and railways could carry fish quickly to market, and the introduction of refrigeration extended the market for fresh fish. With expanded markets came the development of capital, displacing labour in importance, as large plants succeeded to the domestic handling of fish and steam trawlers replaced sailing vessels. The fishery was seriously affected by the change to large-scale organization, by technical changes, and by increased demand leading, as in the case of oysters, to depletion-and the need for conservation. On the other hand, specialization again became pronounced. The important canned lobster industry followed decline in exports of dried cod, and was in turn followed by the live lobster trade in areas adjacent to the American market. The herring fishery became more important in the Grand Manan area and smelts on the gulf shore of New Brunswick .

With the emergence of industrial Canada after 1900, labour organization advanced rapidly, the number of locals increasing from one thousand in 1902 to over two thousand in 1913. Labour legislation became more important. Factory Acts were passed in Ontario , Quebec , Manitoba , and Nova Scotia, and in 1900 a federal Department of Labour was erected. The Industrial Disputes Investigation Act was passed in 1907, making a strike or lockout illegal until a report could be made by a board of investigation and conciliation. Combines in restraint of trade became more serious, with numerous amalgamations which followed the short depression of 1907; but legislation was far from effective.

The Post-War Period.

The period of rapid expansion which ended in 1914 was followed by a recession at the beginning of the World War, increased economic activity to meet war demands, a short post-war slump, the boom of the twenties, and the depression of the thirties. The Grand Trunk Pacific and the Canadian Northern, which had been built with the expectation that, like the Canadian Pacific Railway, they would carry great numbers of immigrants and great quantities of wheat, were struck by the sudden fall in immigration and capital imports, and came into the hands of the government, to be consolidated in 1922 with the Intercolonial and the Grand Trunk as the Canadian National Railways. The boom period of the twenties was supported by the speculative activity of the New York market and by profound technological changes. The Panama canal completed in 1914 became an outlet for wheat from Alberta and lumber from British Columbia . The rapid increase in the use of the gasoline engine brought the development of the motor car, the truck, and the tractor for use in western wheat fields and the airplane for northern exploration. The increasing use of cars and trucks necessitated the construction of roads and hotels to accommodate the growing tourist traffic, and construction piled up provincial debts, while trucks and automobiles gave the railways serious competition. Completion of the Hudson Bay Railway to Churchill and of the Temiskaming and Northern Ontario Railway to Moose Factory facilitated the work of the prospector in covering large unexplored areas of northern Canada and led to the development of mining in the Bear lake area and at Flin Flon. The Welland Ship Canal strengthened the competition of Montreal for the wheat traffic.

In British Columbia , war demands for zinc provided support for elaborate investigations to solve the problem of complex ores, particularly of the Sullivan mine. Success depended on rapid expansion of hydro-electric power, and this in turn supported the fertilizer industry. Fruit-raising, lumbering, and fishing responded to cheaper transportation, and Vancouver and New Westminster grew to meet the new demands. The halibut fishery developed from Prince Rupert , and the effects of rapid exploitation were evident in conservation measures, notably in the Halibut Treaty, as they were in forest regulations and in the closing down of mines in the Rossland and Boundary districts.

Expansion of wheat production in the prairie region accompanied opening of the northern districts, particularly in Alberta , and rapid construction of branch lines. New varieties of early maturing wheat and export by Vancouver hastened development in the Peace river region. Attempts to encourage wheat production during the War led to formation of the Wheat Board, which was followed by rapid growth of the co-operative movement in the pools after 1924. A sharp decline in price with the depression necessitated government guarantees and the establishment of a new Wheat Board in 1935. Drought, with the resultant soil-drifting and poor crops, has left barren many regions which had been cultivated for a generation, thrown many thousands of farmers on provincial and federal relief, and increased the difficulties of the railways.

In the St. Lawrence region, mining continued to expand in the case of nickel during the War and the boom period and in the case of gold during the depression. Post-war problems of the nickel industry were solved with increased industrial use; the Kirkland Lake development was followed by Noranda and construction of a smelter for handling copper gold. The Patricia district and northern Manitoba became the scenes of new activities. Mining development implied expansion of hydro-electric power plants at important sites such as at Quinze and Abitibi Canyon, or a shift of power from declining camps such as Cobalt to rising camps such as Kirkland Lake .

Expansion of the newsprint industry in the years before 1914 was temporarily checked at the outbreak of the War, but in the post-war period proceeded at an even more rapid rate. Exhaustion of supplies of pulpwood and relatively greater demand from the industrial areas of the United States for power supported the migration of capital and labour to exploit Canadian resources, particularly those of Quebec . The depression brought acute financial difficulties and numerous reorganizations. In Ontario the Abitibi Pulp and Paper Company, of which the main plant at Iroquois Falls was completed during the War, absorbed a large number of smaller companies, and in Quebec the International Pulp and Paper Company with plants at Three Rivers and near Ottawa dominated the situation. In the Maritimes the lumber industry, suffering from competition from British Columbia , shifted to an increasing extent to the pulp and paper industry. Smaller plants were built at points such as Mersey in Nova Scotia and Dalhousie in New Brunswick .

The effects of continued industrial expansion in the St. Lawrence region appeared in continued emphasis on the dairy industry and increased consumption of dairy products. Improved roads facilitated expansion of the canning and dried milk industries and growth of creameries. Urbanization implied expansion of a wide variety of industries, increased consumption of hydro-electric power, and increase in power production.

The Maritimes were less fortunately situated for the post-war boom than for the pre-war boom, with the result that iron and steel industries - the manufacture of railway cars and rails - and coal-mining felt the effects of the depression acutely. Industrial disputes and financial difficulties became increasingly serious, and competition from the St. Lawrence was felt more severely. Expansion of the Iceland fishery through the use of the trawler narrowed the market for Nova Scotia fish and hastened the decline of the Lunenburg fishery. Increasing emphasis on the domestic market has been followed by regulations restricting the trawler and by attempts to widen the internal market by improving transportation to the St. Lawrence and to increase the market for live lobsters in the United States . Apple-production has felt the effects of competition in the British market, and potato exports have suffered from American tariffs.

The sustained character of depression in Canada has accentuated numerous problems. Relative exhaustion of natural resources has been followed by increasing attention to conservation measures. The problem of debt, which became acute with the War and increased as a result of expansion of railways and roads, has been followed by readjustment on a large scale varying from relief measures to creation of a central bank. The burden, as shown in railway rates, tariffs, and interest charges, has been adjusted in part by such legislation as the Maritime Freight Rates Act, and by special subsidies, subventions, and guarantees. Inadequacy of the tariff has brought increase of the income tax. Social legislation and its costs have accentuated the demands for readjustment of federal-provincial relations. Attempts to widen markets as a basis of relief have been evident in the Ottawa Agreements and reciprocity with the United States . The depression has been characterized by numerous attempts, as shown in royal commissions on the railways, banks, and price-spreads, to gain an understanding of the methods of operation of the Canadian economy and to introduce extensive control legislation. A definite interest in economic problems and in economic history has become evident, and this may eventually hasten the development of a more adequate understanding of the difficulties of a government attempting to meet the divergent problems of a continental and a maritime area dependent in varying degrees at various stages of the business cycle on exports of raw materials in a world market.

Bibliography.

The only general treatment of Canadian economic history is to be found in Mrs. M. Q. Innis, An economic history of Canada (Toronto, 1935), in Mrs. L. C. A. Knowles, Economic development of the overseas Empire, vol. II ( London, 1930), and in the chapters relating to economic history in the Cambridge history of the British Empire , vol. vi (Cambridge, 1930), and Canada and its provinces (23 vols., Toronto, 1914). Reference should be made also, however, to H. A. Innis, Problems of staple production in Canada ( Toronto , 1933), S. A. Cudmore, History of the world's commerce ( Toronto , 1929), H. Heaton, A H istory of Trade and Commerce, with Special Reference to Canada ( Toronto , 1928), and Statistical contributions to Canadian economic history ( Toronto , 1931). A number of valuable papers and an extensive bibliography will be found in Contributions to Canadian economics, vols. i-vii ( Toronto , 1928-34) ; the bibliography is continued in the Canadian Journal of Political Science and Economics ( Toronto , 1935-). Illustrative documents are to be found in H. A. Innis, (ed.), Select documents in Canadian economic history, 1497-1783 (Toronto, 1929), and in H. A. Innis and A. R. M. Lower (eds.), Select documents in Canadian economic history, 1783-1885 (To ronto, 1933). Current statistics are contained in the Canada Year Book.

[ Note from the editor : I highly recommend the web course in Canadian Economic Development by Professor K. J. Rea of the University of Toronto . The web site contains substantial notes for each of the 18 chapters. These cover all major periods in Canadian history, from New France to the most recent developments. Aside from the notes, each chapter has an audio file lasting from 25 to 60 minutes where professor Rea explains the subject at hand. These audio files are around 2 mb and download rapidly if you have a fast modem.

You will also find substantial notes, slides, maps and articles on Canadian Economic History at this university site.]

Source: W. Stewart WALLACE, "Economic History", in The Encyclopedia of Canada , Vol. 3, Toronto, University Associates of Canada, 1948, 396p., pp. 153-167. |

© 2004

Claude Bélanger, Marianopolis College |

|