History

|

Newfoundland History |

|

Newfoundland History

Early Colonization and Settlement Policy in Newfoundland

[This text was written in 1950. For the full citation, see the end of the document. Images, text in brackets [...] and images have been added to the original text by Claude Bélanger.]

NEWFOUNDLAND from the beginning has lived by the products of the sea and its early history is essentially that of the cod fishery. For more than a century before the establishment of French or English colonies in North America the fishermen of Western Europe came year after year to Newfoundland to fill their boats with cod for the markets of the Old World .

Of the earliest exploration and discovery of Newfoundland little is known. It is generally accepted that Norsemen from Greenland visited Newfoundland and Labrador as early as 1001 A.D., and there is a tale that men of the Channel Islands, in the latter part of the 15th century, were blown westward off their course until they came to a strange land where the sea was full of fish. There is better evidence that the Island was discovered in 1497. In the previous year an Italian navigator, John Cabot [consult also the Dictionary of Canadian Biography; henceforth DCB], then living in England and engaged in the fish trade with Iceland, obtained from Henry VII a charter giving him and his sons authority to "sail to all parts, countries and seas of the East, the West and of the North, under our banner and ensign . and to set up our banner on any new-found-land".

Cabot set sail from Bristol on May 2, 1497, in a little ship of 50 tons, the Matthew, with a crew of 17. After sailing 53 days they came, on June 24, St. John's Day, to the shores of a new land in the west. There are no records to establish the first spot in North America seen by Cabot, but in Newfoundland there is a long-established tradition that his landfall was Cape Bonavista. An entry in the Privy Purse of England records the discovery: "August 10, 1497: To hym that found the new isle, 10£".

Cabot returned to England with tales of a sea so full of fish that they could be taken "not only with the net but also with a basket in which a stone is put". His stories stirred a ripple of excitement in England which quickly spread to the Continent, for fish in those days commanded higher prices than meat. The records show that a few English fishing vessels accompanied Cabot on his second voyage in 1498 and that the English fished in Newfoundland waters continuously from that date. They were soon joined by the Portuguese, whose famous navigator Corte Real [consult the biography at the DCB] explored the Island's coast in 1501, by the French from Normandy and Britanny [sic], and, about the middle of the 16th century, by the Spanish Basques .

Early Colonization and Settlement Policy

In the summer of 1583 St. John's was visited by an expedition of four ships commanded by Sir Humphrey Gilbert [his biography at the DCB], who carried a commission from Queen Elizabeth to sail the seas and take lands under her banner. The expedition called at St. John's because it was known that provisions could be obtained there. Shortly after his arrival Gilbert set up his tent on a hill overlooking St. John's harbour, and caused the masters and chief officers of the ships of all nations there to attend while he solemnly read aloud his commission and formally took possession of the Island in the name of the Queen. Newfoundland thus became England 's first possession in North America and her oldest colony, although England 's title was disputed from time to time until the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713.

Although it is believed that some fishing crews wintered on the Island as early as twenty years before Gilbert took possession, no formal attempt at colonization was made until early in the 17th century. Sir Francis Bacon and his associates formed the Newfoundland Colonization Company and in 1610 sent John Guy [his biography at the DCB] to found a colony in Newfoundland. Guy carried with him a Charter from James I containing explicit instructions regarding the purchase of fish and cod oil, the cutting of timber for export, the raising of sheep and other matters. He settled with his 41 colonists at Cupids (then Cuper's Cove) in Conception Bay. Houses, stores and wharves were built and a fort erected. Further inland a farm and a mill were established. In 1613 the first white child was born in Newfoundland .

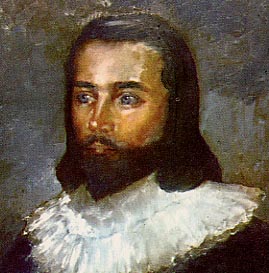

John Guy

Guy seems to have established the first contact with the native Indians of Newfoundland, the Beothucks (Beothics) [consult the biography of David Buchan who was one of the last to have explored Newfoundland and been in contact with the Beothucks] who are believed to have been a distinct tribe and not part of any of the larger tribes on the mainland. Little is known of them, for their relations with the white men, friendly at first, soon degenerated into mutual distrust and persecution, which became so bad that in the middle of the 18th century the early governors of Newfoundland issued proclamations threatening to punish anyone known to kill a Beothuck. The last Beothuck seen was a woman called Shanawdithit [see her biography at the DCB] who was found starving in a wigwam and taken to St. John's . According to her there were only 13 Beothucks left in 1823, and after her death in 1829 no further trace of them was seen.

From the first the colonists had to contend with the hostility of the West-of-England fishing merchants, who did not welcome the competition of permanent settlers. When the merchants' petitions to the King failed, they resorted to violence and persecution destroying the settlers' property in an effort to remove them. The colonists also suffered from attacks by pirates, who swooped down periodically and carried off men and goods. In spite of these discouragements the settlement lasted until about 1628.

Before 1620, other settlements had been established by Royal Charter in what is now the Avalon Peninsula - one at Bristol's Hope ( Harbour Grace); one near St. John's; Sir William Vaughn's [alternate spelling Vaughan; see his biography at the DCB] colony with headquarters at Trepassey; Lord Falkland's two colonies, one in Trinity Bay, the other in the southern part of the Peninsula; and Lord Baltimore's colony at Ferryland.

The separate colonies were merged into one under a Royal Grant of 1637, giving the whole island to Sir David Kirke [consult his biography at the DBC], the Duke of Hamilton and their associates. Kirke at once began to raise money by charging rent for "stages" and "rooms", [1] selling tavern licences and levying taxes on the fish caught not only by the English but by foreigners. The complaints of the settlers led to an investigation and Kirke was dismissed for having acted dishonestly towards his partners. This was the last official attempt to colonize the Island.

The first permanent colonists were hard-working fishermen from the West of England who chose to live in the Island in order to carry on their trade of fishing. The first permanent settlement, as distinct from the short-lived chartered colonies, grew up in the neighbourhood of St. John's, from Petty Harbour around Cape St. Francis to Holyrood in Conception Bay. From the first St. John's was the chief port and trading centre.

About the middle of the 17th century English colonial policy underwent a profound change. The new policy, known to historians as " the Old Colonial System", lasted until well into the 19th century. Under it the development of the colony was managed with a view to enhancing the power and wealth of England . Settlement was encouraged in colonies where land cultivation promised to produce new commodities of trade, as in the West Indies which produced sugar or Virginia and Maryland which produced tobacco. On the other hand, settlement was discouraged where it appeared to be against England 's interests.

In the case of Newfoundland, settlement appeared to threaten the monopoly control of the fishery acquired by West-of-England fishing centres. The Government also came to look upon the annual fishing voyages from England as an excellent training system for potential recruits for the Navy. Moreover, settlement in Newfoundland entailed responsibilities on the home authorities for defence in time of war. Thus from the time of Charles I until the early 19th century the prevention of settlement in Newfoundland was a fixed policy, the Island being considered rather as a "great ship moored near the Banks . . . for the convenience of English fishermen".

The regulations passed by the Star Chamber in 1633, and confirmed and made more stringent under Charles II in 1670, forbade English ships to carry to Newfoundland intending settlers or to leave behind any of their crews. The settlers already there were forbidden to cut wood, to build within six miles of the shore or to take any fishing places until the fishermen from England had arrived. Under these rules planters who had lived for years in the Island, who had cleared land and built homes, were deprived of all property rights.

In spite of these laws settlement did take place gradually. The laws were difficult to enforce, and the settlers built their houses in small coves where they could escape detection. There they brought up their families, raised vegetables and fished, clinging tenaciously to the land they had adopted in spite of all efforts to remove them. [For a further examination of the impact of mercantilism on Newfoundland, consult this text by professor Robin Neill of the University of Prince Edward Island ]

[1] A "room" is the portion of shore on which a fisherman cures his catch and erects the necessary huts and flakes and a "stage" is a platform on which fish is dried.

Source: GOVERNMENT OF CANADA , Newfoundland . An Introduction to Canada's New Province, Published by authority of the Right Honourable C. D. HOWE, Minister of Trade and Commerce, prepared by the Department of External Affairs, in collaboration with the Dominion Bureau of Statistics, Ottawa, 1950, 142p., pp. 15-41.

© 2004 Claude Bélanger, Marianopolis College |