History

|

Newfoundland History |

|

Newfoundland Fisheries

(to 1949)

[This article was written in 1949. For the full citation, see the end of the text. Links and images have been added to the original document by Claude Bélanger. For recent developments, consult this article. Further information on the French Shore issue may be found elsewhere at the site as well as a discussion of American fishing rights in the waters of Newfoundland. The devastation that the cod moratorium has created is documented in images elsewhere at the site.]

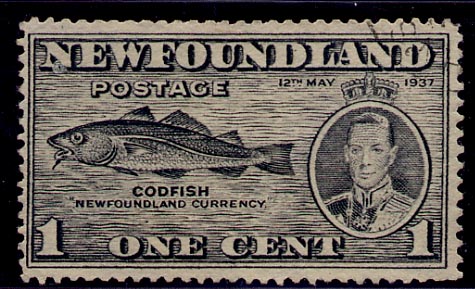

The cod fisheries have played a dominant rôle in the economic, political, and social history of' Newfoundland. The island is located in the northern part of a vast area, extending from New England to Labrador, in which cod is to be found in large numbers. Sharply affected by seasonal changes, it very early became the centre of a summer fishery in which the relatively smaller sizes of cod were taken and dried with solar heat and smaller quantities of solar salt.

The discovery of quantities of cod by John Cabot from Bristol , in 1497, was followed by the rapid exploitation of the fisheries by the Portuguese, French, and Spanish from countries with cheap supplies of salt. By the first half of the sixteenth century French fishermen, according to the account of Jacques Cartier, were prosecuting the industry along the east coast of Newfoundland to the straits of Belle Isle and had developed the green fishery on the banks. In the second half of the century, decline of the Spanish fishery and defeat of the Spanish fleet were followed by a rapid expansion of the English fishery in Newfoundland. The interest of the east coast of England in the Iceland fishery was supplemented by the development of the English fishery from the west country (Cornwall, Devon, and Dorset) to Newfoundland. English fishermen were compelled to depend on Portuguese, and later, French supplies of salt, and English ships began to develop a trade to centres in Newfoundland, particularly in the Avalon peninsula , acquiring supplies of salt and fish from European fishermen. After the defeat of the Spanish armada they acquired supplies of salt from France, went to Newfoundland and returned with dried fish for the domestic market, and in the last decade of the sixteenth century, a surplus of dried fish was exported to Europe . As a result of the rise in prices following the import of treasure from the new world, the Spanish fishery declined, and the English fishery and trade emerged to take advantage of supplies of specie.

Prosecuting the fishery in Newfoundland and returning to the west country with dried fish for export to Europe was gradually displaced by the practice of carrying fish directly from Newfoundland to European markets, especially in the. Mediterranean area. Fishing ships proceeding to Newfoundland early in the spring, carrying on the fishery during the summer months and taking the product to European markets, were faced with the problem of transporting large numbers of men to Newfoundland for the fishery, then to the European markets and back to the west country. Colonizers, represented by the London and Bristol Company (1610), proposed to establish a settlement which would enable men to stay over the winter, to carry on a resident fishery, and to provide cargoes for sack ships for the Mediterrenean markets. This proposal and others similar to it were ruthlessly defeated by west country fishermen who insisted on the rights of a free fishery which gave the first arrival each year the position of admiral for the season. The difficulties of developing agriculture, to supply food for winter settlements, further restricted the growth of settlement in Newfoundland and favoured the migration of population to New England.

The rise of New England and its demand for European goods led to the growth of trade with Newfoundland . As a result of this increase in trade, settlement began to expand in spite of continued and more vigorous efforts of the west country to check it. Partly as a result of restrictions on settlement imposed at the instigation of the west country, men known as byeboatmen began to dominate the industry. They were brought on the fishing ships as passengers each spring, operated a fishery in Newfoundland independently of the fishing ships, and sold their product before their return to England in the autumn. The fishing ships were in a sense compelled to serve as sack ships carrying passengers to Newfoundland and the finished product to European markets.

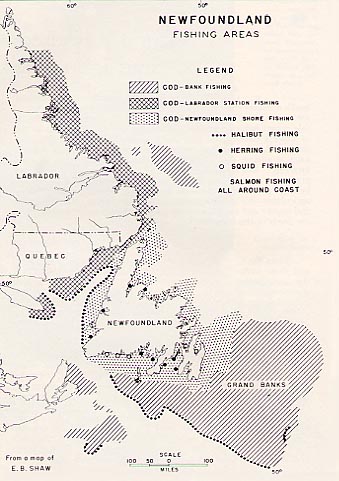

Map outlining the principal species and the main areas where

Newfoundland fisheries were carried out until the

establishment of the moratorium of 1992.

[Consult the issue of the Canadian Geographic Magazine on this subject]

Following the treaty of Utrecht, in 1713, New England became even more important as a base of supplies for Newfoundland and as a support to growth of settlement. Fishermen were attracted to New England and to the more profitable operations carried on by byeboatmen, and fishing ships were compelled to rely on resident fishermen, particularly on Irish labor which filled the gap created by emigration. The growth of settlement was accompanied by extension to the south to occupy territory centering about Placentia, which had been vacated by the French after 1713, and by the development of the bank fishery. St. John's became the centre of a resident fishery; fishing ships became to an increasing extent sack ships, or retreated, on the development of new areas, beyond the effects of competition from St. John's.

After the treaty of Paris, Labrador was annexed to Newfoundland . In 1765 regulations favoured the development of its fisheries by fishing ships, but in the Quebec Act of 1774 Labrador was returned to Canada, and attempts were made to re-establish the system of grants existing before the introduction of a free fishery. Expansion to the north was accompanied by the development of the fur trade and of the salmon fishery. The outbreak of the American revolution cut off supplies of goods from New England. Palliser's Act in 1775, and other legislation, attempted to offset the effects by establishing a system of bounties which improved the position of fishing ships and restricted the resident fishery. [See the British Report on Newfoundland fisheries in 1776.]

In the treaty of Versailles the French abandoned fishing rights from Cape Bonavista to Cape St. John in return for rights along the coast from Point Riche to Cape Ray . They remained in possession of St. Pierre and Miquelon. During the long period of wars ending in 1815, Newfoundland became increasingly a centre of settlement, and the fishing ships practically disappeared. Territory north of Cape Bonavista was rapidly occupied. The seal fishery emerged and expanded rapidly. Until New England and France were able to revive their fishing industries, Newfoundland had an important market advantage which was evident in higher prices. The Maritime provinces replaced New England as a base of supplies, and the migration of labor to New England was checked.

Topsail Beach with its fishflakes around 1905

The increasing importance of settlement created demands for the extension of political institutions. In 1832 provision was made for representative government, and emergence of responsible government in 1854 was accompanied by the development of resistance to French interests in Newfoundland . In an attempt to reestablish the fisheries, France introduced a system of substantial bounties which accelerated the use of the trawl system of fishing, in which a line to which was attached a large number of hooks was set out and visited at frequent intervals. The system required large quantities of bait, which was purchased to an important extent by fishermen in St. Pierre and Miquelon from settlements on the south shore of Newfoundland , and attempts were made in Newfoundland to check competition from the French fishery by imposing restrictions on exports of bait. An agreement between France and Great Britain in 1857, designed to settle the difficulties arising from conflicts between French and English fishermen, was followed by protests from Newfoundland and recognition of the fact "that the consent of the community of Newfoundland is regarded by Her Majesty's government as the essential preliminary to any modification of their territorial and maritime rights". Recognition of Newfoundland's control over natural resources was followed by various measures designed to restrict the French fishery and to extend Newfoundland 's territorial rights. In 1881 Great Britain conceded territorial jurisdiction over the "French shore" to the Newfoundland government. Newfoundland refused to ratify an agreement between France and Great Britain in 1885 and passed bait legislation in 1887. France and Great Britain established in 1889 a modus vivendi which was renewed from year to year and was the object of continued protests from Newfoundland . The controversy became more acute with the growth of a lobster fishery and was finally ended by the purchase of French rights by Great Britain in 1904.

Newfoundland fishing fleet leaving for the Grand Banks

With responsible government Newfoundland pressed for exclusion not only of France but also of the United States , Canada , and Great Britain, from the fishery. Following the reciprocity treaty (1855-1866) with the United States , Newfoundland introduced and enforced regulations which rapidly brought to an end participation of the United States in the Labrador fishery. During the period of the treaty of Washington (1873-85), Newfoundland became increasingly aggressive against American infringements and after its termination Newfoundland attempted to negotiate the Blaine-Bond convention with the United States , but was defeated by Canadian intervention. A second attempt to secure reciprocal arrangements in the Hay-Bond treaty was defeated by the American senate and was followed by renewed attacks on participation of Americans in the Newfoundland fishery. Disallowance of legislation against the United States by Great Britain was followed by protests from Newfoundland and submission of the whole problem to the Hague tribunal, which reported in favour of the position of Newfoundland . Finally, an attempt on the part of Canada to secure a broad interpretation of rights on the Labrador was defeated in a privy council decision of 1927.

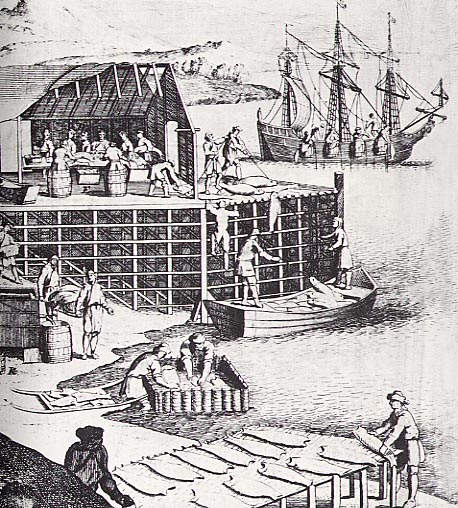

Detail from Eric Mill's map of North America published 1712-1714.

According to its author, it shows a view of a stage and the manner of fishing for curing

and drying cod on the island of Newfoundland. The popular scene contains

several inaccuracies: the type of ship used for fishing, the fact that cod

and seals are harvested at the same time, the fish stage itself, etc.

Exclusion of fishermen from foreign countries from Newfoundland facilitated expansion of the local fisheries to the west coast and on the Labrador . The high prices of cod during World War I were followed by a decline and by increasing competition in European markets from cod produced more cheaply by steam trawlers in Iceland and elsewhere; hence Newfoundland trade shifted to West Indian and South American markets. Problems of centralized marketing in purchasing countries were met by the establishment of marketing boards. Recent developments have been the extension of marketing organizations, encouragement of the fresh fish industries, exploitation of types of fish other than cod, and establishment of a research centre. The number of people engaged in the fishery decreased, between 1921 and 1945, from 65,000 to 32,000. [For a discussion of the recent developments in Newfoundland fisheries, consult this web site. Much material can be found in this bibliography.]

For a recent bibliography of the subject, see the appendix to R. A. MacKay (ed.), Newfoundland economic, diplomatic, and strategic studies ( Toronto, 1946).

Source: W. Stewart WALLACE, ed., The Encyclopedia of Canada. Newfoundland Supplement, Toronto, University Associates of Canada, 1949, 104p., pp. 39-43. Some minor mistakes have been corrected. The text has been reformatted for the web edition.

© 2004 Claude Bélanger, Marianopolis College |