History

|

Newfoundland History |

|

Newfoundland Law

(to 1949)

[This text was written in 1949. For the precise citation, see the end of the document. Links and images have been added by Claude Bélanger.]

The first attempt to create a formal court of justice in Newfoundland was in 1615, when Captain Richard Whitbourne was sent out from England with a commission from the high court of admiralty with authority to impanel juries and to make enquiry upon oath of sundry abuses and disorders committed every year among the fishermen on the coast. In Trinity harbour, 100 miles north of St. John's , he called together the masters of the English ships lying there and held the first court of admiralty in Newfoundland . The masters of 170 English ships, who acted as grand jurors, inquired into the alleged disorders and delivered their presentments to the court, that is to Whitbourne, who transferred them to the high court of admiralty in England. The presentments were summarized under twelve heads. Among them were: (1) non-observance of Sabbath day; (2) injury to harbours by casting into them large stones; (3) destroying fishing stages and huts; (4) monopoly of convenient spaces; (5) entering the services of other countries; (6) burning woods; (7) idleness, parent of all evils. The jurors declared these disorders should cease, but this commission was doomed to failure from the start, for Whitbourne had no bailiff to serve process, no room to hold court, and no power whatever to enforce his decisions.

It may be remarked here that the earlier colonies were for a long time treated by the kings as their exclusive property and not subject to the jurisdiction of the state. When the house of commons attempted to pass laws for establishing a free right of fishery on the coasts of Virginia, New England, and Newfoundland, the house was told by the ministers of the crown that it was not fit to make laws for those countries which were not yet annexed to the crown, and that the bill was not proper for the house, as it concerned America. Hence it was the Star Chamber - the council of the king - that established rules and regulations for the governance of the fisheries of Newfoundland, after being petitioned by the merchants and owners of ships in the west of England, and which assumed the power of legislating with reference to murder and theft committed on the island by directing that offenders should be carried to England to be tried before the earl marshall.

Act 10 and 11 of William III.

In 1698 there was passed the famous or notorious Act - the Act 10 and 11 of William III for the regulation of the trade and fisheries in Newfoundland . There had long been jealousy between the merchants on the one hand and the planters and inhabitants on the other; and the merchants regarded this Act as the soundest policy pursued in relation to the fishery. It provided that courts of oyer and terminer [see this page for its application to Quebec] in any county in England should have jurisdiction in cases of robberies, murders, felonies and all other capital crimes done or committed in Newfoundland. By this Act was established the jurisdiction of the fishing admirals; it was, as Prowse says, "the surrender of the entire control of the colony, including the administration of justice, into the rude hands of a set of ignorant skippers, who were so illiterate that out of the whole body of these marine justiciaries only four could be found at all to sign their names."

The fishing admirals were given authority to hear and determine controversies between the masters of fishing ships and the inhabitants or any byeboat keeper concerning the right and property of fishing rooms, stages, flakes or any other buildings or convenience for fishing or curing fish. If anyone thought himself aggrieved by a judgment he might appeal to the commander of any of the king's ships belonging to the convoy. This was a civil judicature of a limited sort, for the merchants were not subject to it. Debts still remained without any mode of recovery, and the admirals were not authorized by the Act to impose penalties of any kind.

The admirals were men who were employed in the fishing and often did not attend to their judicial duties. The commanders of the king's ships often found they had to force them to hold courts and often held court with them. Finally the commanders made themselves not only a court of appeal but constituted themselves into an original one, for they slowly dispensed with the attendance of the admirals, and so succeeded to a complete original exercise of judicial authority in the place of the admirals.

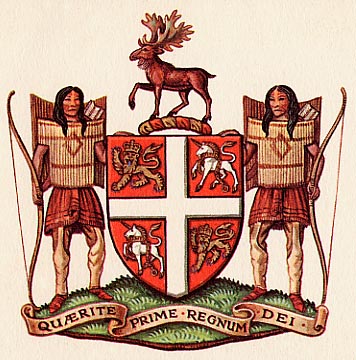

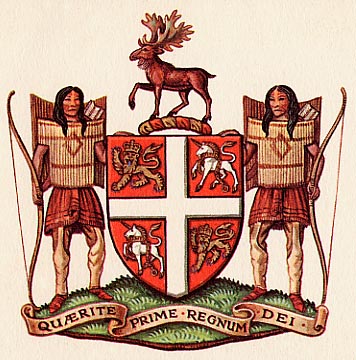

Coat of Arms of Newfoundland featuring Beothuk Indians

Justices.

After the treaty of Utrecht (1713) the number of planters and inhabitants increased, and they began to feel the want of a government or administration of justice more efficient and impartial than that provided by the fishing admirals. Disorder and anarchy had prevailed, particularly in the winter months. In 1728 the first governor of Newfoundland was appointed, Captain Henry Osborne, who had authority to appoint such respectable persons as he should think most proper to act as justices of the peace and to hold courts of record, hearing and determining on all matters in dispute between parties according to the laws of England, not extending to capital offences, which were as before to be tried in England. But the hand of the merchants was again seen. Osborne was warned that neither he nor his justices were to do anything contrary to Act 10 and 11 of William III, nor to interfere in any way with the privileges of the admirals as defined by that Act. Still, Osborne acted with great energy: he appointed justices and constables, divided the island into districts, and erected prisons and stocks. However his influence was weakened by his departure at the end of the fishing season, and the justices found it difficult to maintain their power against the influence of the fishing admirals. Birkenhead says, in his Story of Newfoundland, "The admirals, whose wits seemed to have been sharpened by judicial practice, insisted that their own authority was derived from a statute whereas those of the justices merely rested on an order in council."

The contest between the merchants and fishing admirals on one side and the governors and justices on the other side continued for a half century. The admirals declared that the justices were only winter justices, and had authority only when the admirals had returned to England . They seized, fined, and whipped at their pleasure, and entirely set aside the findings of the newly created justices. But in spite of the support of the merchants, this authority, lodged in such ignorant hands, gradually lessened; and, as the admirals sank into inactivity and contempt, the commanders of the king's ships rose in importance till finally the administration of justice on the island came to be expected from no one but the commanders when they came to the island in the summer season.

Even as the commanders took cognizance of cases as a court of first instance, though really only having the right of hearing appeals, so they began to enlarge their scope further, apparently on the principle that judges have the quality of enlarging their jurisdiction. Soon they were taking cognizance of debts contracted, and holding courts in which they enquired of, heard, and determined all possible causes of complaints. Owing to the support they received from the governors they were enabled to maintain the jurisdiction they had assumed, and the governors conferred on them the title of "surrogates".

While the surrogates were administering justice in other parts of the island, the governor had his court in St. John's; the governor arrogated to himself the same jurisdiction as his surrogates, and cases of all kinds were tried in his court. Sometimes a governor went further than propriety would allow, as for instance, when he presided over the sessions of the justices, although it was from his authority that the commission of the justices issued. However, the foundation of this procedure got a rude shaking. Some persons discontented with a judgment made by Governor Edwards in court and carried into execution by the sheriff, sued him, on his return to England, at Exeter, for trespass to their property. On account of this event his successor, Sir John Harvey, was advised not to sit in court.

In the year 1765, on the establishment of a custom house in St. John's , there was formed in that city a court of vice-admiralty, which was the court of revenue in the plantations. This court, in the absence of the governor during the winter, entertained complaints on other matters than those peculiarly belonging to it; it only followed the example of the court of sessions where the justices had allowed the hearing of matters of debt and other subjects of a civil nature. It was on account of this usage that the Statute 15 George III, in 1775, gave to the court of vice-admiralty and the sessions authority to determine disputes concerning the wages of seamen and fishermen, but this jurisdiction was taken away by Statute 26 George III owing to the unfavourable impression that had been made respecting the practice which had prevailed in that court.

When Admiral Milbanke in 1789 was setting out for Newfoundland on his first trip, he was advised by his secretary to create a court of common pleas with regular judges instead of justices of the peace, and he did appoint such a court which transacted business.

The English authorities came at last to the realization of the necessity of placing the court on a sound basis and endowing it with high authority by constituting it under an act of parliament and giving it as much force, in the eyes of the people, as the judicature enacted by the Act of William III.

Accordingly, in 1791, the House of Commons passed an Act creating a court designated " the Court of Civil jurisdiction of our Lord the King at St. John 's in the Island of Newfoundland ". This was the first Judicature Act and it constituted a court of civil jurisdiction with power to decide summarily on matters of debts, contracts, and trespasses relating to the person or personal property only. This was presided over by Chief Justice Reeves and was to continue for one year. It was continued under the proper name of "The Supreme Court of Judicature of the Island of Newfoundland " which established a supreme court of both civil and criminal jurisdiction and also surrogate courts of civil jurisdiction. This Act, which was altered in a few points by the Act of 1793, continued in force by annual renewal till 1809 and served as the model for the Act of 1807 which was in its provisions, with some exceptions, similar to the Act of 1824.

Judicature Act.

At first there was only one judge who was known as the chief justice, and it was not until the Act of 1824 that three judges formed the court as at the present day, namely, the chief justice and two puisne judges. The first judges, apart from Reeves, were not learned in the law. It was finally recognized in England that the altered circumstances of the country required an improved system of law, and in 1824 the judicature Act was passed, the basis for the law as now administered. It came into effect on January 1, 1826.

In 1832 a constitution was granted to Newfoundland similar to the ones granted to the other North American colonies, and in 1833 the first session of the house of assembly under representative government was held.

The Law Society was formed by an Act of the local legislature in 1834 and the day of the layman in the courts, either as judge, or lawyer, was over.

There have been some changes in the administration of law since 1824 but they have been minor in comparison with the previous changes. The Supreme Court remains, in its constitution, practically the same. It carries on its work now under the judicature Act of 1904, embodied in consolidated statutes of 1916.

The surrogates' courts and the quarter sessions, which were the lower courts, have ceased to exist and the magistrates' courts have taken their place. There is another special court, the central district court, which is a court of civil jurisdiction in St. John's and has a judge, known as the judge of the central district court, with an assistant known as the clerk of the peace.

Property.

There is no real property in Newfoundland . All landed property is, by a Statute of 1834, declared chattels real. This Act is set out in the Consolidated Statutes of Newfoundland, Third series (St. John's, 1919), and reads thus:

1. All lands, tenements and other hereditaments in Newfoundland and its dependencies, which by the common law are regarded as real estate, shall, in all Courts of justice in this Colony, be held to be " chattels real", and shall go to the executor or administrator of any person or persons dying seized or possessed thereof as other personal estate now passes to the personal representatives, any law, usage or custom to the contrary notwithstanding.

2. All rights or claims which have heretofore accrued in respect to any lands or tenements in Newfoundland, and which have not already been adjudicated upon, shall be determined according to the provisions of the foregoing section; but nothing herein contained shall extend to any right, title, or claim to any lands, tenements or hereditaments, derived by descent, and reduced into possession before the twelfth day of June, anno Domini eighteen hundred and thirty-four.

There were two judgments after the Act of 1834 wherein it was declared that primogeniture existed here previous to the Act. One of these, Wallbank v. Ellis is mentioned in Newfoundland Law Reports , 1846-1853. However, there were two cases heard before the passing of the Act which decided otherwise, namely, Williams v. Williams, Select cases in the Supreme court of Newfoundland (St. John's, 1829, p. 120), where judgment was given by Chief Justice Forbes, and Kennedy v. Tucker, where judgment was given in 1792 by Chief Justice Reeves.

In the latter case the eldest son claimed succession as heir at law to a plantation (land with erections for fishery purposes) of his intestate father. It was held that the property should be equally divided, on the grounds that land and plantations in Newfoundland were nothing more than chattel interests and should be distributed as such.

The decisions of Reeves and Forbes were pronounced during the time that Acts 10 and 11 William III Chapter 25, and 15 George III Chapter 21, were in force. It was the policy of these Acts that Newfoundland was to be considered as a fishery only, and not a colony or plantation, so that occupancy of the soil could only be temporary. In the Act of 1834 there is a preamble setting out that whereas doubts had arisen whether primogeniture ever existed in Newfoundland, the Act was passed to remove those doubts.

Dower and courtesy do not exist in this country.

While there cannot be a remainder in personal property, yet Newfoundland law must deal with reversions, remainders and executory interests.

All property will naturally pass to the personal representative on intestacy. The creation of future interests in land can be done by means of executory limitations, it has been decided, without the intervention of trustees.

It must be assumed that to create successive interests in land by alienation inter vivos, the intervention of trustees is necessary.

As to execution, land, being chattels real, can be levied on and sold under a writ of fiere facias.

Constitution.

Before entry into the Canadian confederation, Newfoundland had what may be called a common law constitution. Newfoundland was instituted by the prerogative of the king, by commission under the great seal, and by royal instructions. Consequently the, Newfoundland legislature could make any law and the courts would take cognizance of any Act except those in violation of matters set out in the instructions to governors.

In civil jurisdiction the law of England, common and statute, as it was in July 1832, prevails. Statutes passed since that date do not apply except statutes such as the Merchant Shipping Act, made specifically referable to Newfoundland, which became the law as fully as if passed in Newfoundland.

Until 1832 the English criminal code applied in Newfoundland; and, in order to obtain the benefit of the very great improvements made in the English criminal code in the 1830's, an act of the local legislature in 1837 was passed whereby all the criminal laws and statutes of the imperial parliament in force in England on June 30, 1837, and all subsequent statutes of the imperial parliament, in amendment or alteration of the criminal law, should within twelve months after the passing, so far as they could be applied, extend to and be the law of the country and its dependencies in all cases.

Back to Newfoundland Politics ...

Source: W. Stewart WALLACE, ed., The Encyclopedia of Canada. Newfoundland Supplement, Toronto, University Associates of Canada, 1949, 104p., pp. 43-55, 62-67. Some minor mistakes have been corrected. The text has been reformatted for the web edition.

© 2004 Claude Bélanger, Marianopolis College |