History

|

Newfoundland History |

|

Political History of Newfoundland

(to 1949)

[This text was written in 1949. For the full citation, see the end of the document. Images, comments under images and links have been added by Claude Bélanger.]

The failure of attempts at formal colonization made by John Guy, Lord Baltimore, and others in the first decades of the seventeenth century did not affect the slow process of colonization by individual fishermen who forsook the common practice of returning to England each fall when the vessels had completed their catch. Indeed, there is evidence to show that even before Sir Humphrey Gilbert's ill-fated expedition of 1583 there were some permanent residents on the island. By 1630 the number of such residents had become sufficiently large to conflict with the interests of west-country fish merchants who wished to retain a monopoly of berths and harbours necessary to successful catching and curing operations. The pressure these merchants could bring to bear on London was strong enough to induce the Star Chamber to issue a series of decrees in 1630 with a view to eliminating the disorder resulting from the friction between permanent fisherman or "planters" and the migratory fishermen from the west country, and, also, to preserve the merchants' monopoly from further encroachments. Of these decrees, by far the most important were: (1) that vessels engaged in the Newfoundland fisheries could not carry from England anyone who intended to settle in the island, and were compelled under pain of heavy penalties to account for all crews taken out in the spring; and (2) that the captain of the first ship to reach a harbour in the spring would be "admiral" of that harbour for the rest of the season, and as such would have the power to settle disputes and administer justice. Subsequently, the English government issued decrees prohibiting the enclosure of land or the erection of permanent buildings.

Fishing admirals. The rule of the fishing admirals extended through the seventeenth and into the eighteenth century, in spite of frequent protests made by the settlers and by visitors from England who realized that the barbarism and anarchy prevailing in the island stemmed chiefly from the iniquitous system of government.

Naval governors . Gradually, and partly because of the repeated attacks on English settlements by the French, who had established a stronghold in Placentia on the south coast, some of the power held by the fishing admirals was transferred to the naval, and later, to the military commanders in the island. In 1729 the British government took the important step of appointing the first governor, a naval officer, Captain Henry Osborne. He was the first of a long list of naval governors among whom were Byng, and Rodney, and the hundred-year period following his appointment is generally known as the period of the naval governors. It was marked by a steady increase in population, gradual establishment of courts of law, and the British government's tacit recognition of its failure to prevent permanent settlement in the island.

Representative government. By the beginning of the nineteenth century the permanent population had reached 20,000, and this growth was accompanied by an increasing demand for some form of representative government. The influx of Irish immigrants during, the first decades of the century, the growth of education, and, above all, the strenuous efforts of a medical practitioner, Dr. William Carson, were the chief factors in intensifying this demand, which, however, was ridiculed and condemned by west country merchants who, even as late as 1817, proposed that the entire population be removed to "Nova Scotia or Canada".

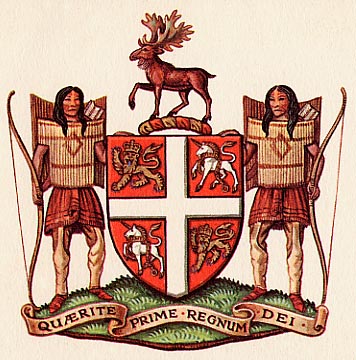

The Colonial Building (as photographed in 1949) was the seat of the

Newfoundland Legislature

Agitation for some measure of home rule in Newfoundland reached a peak around 1830, coinciding with the reform movement in England . In 1832 the British parliament passed a measure granting the island a representative assembly, but providing at the same time for a nominated legislative council. From the first, the two chambers disagreed violently, but this evil was small in comparison with the rekindling of old hostilities between the English Protestants and Irish Catholics, which was to plague the political scene for the next fifty years. Election riots in 1840 so alarmed the British government that it deemed it necessary to suspend the constitution for two years. Following this period a general assembly was created in which members of the two chambers deliberated as one body.

Responsible government. In 1848, again coinciding with the liberal movement in Europe, agitation started anew for the establishment of a responsible government in Newfoundland. By 1854 it had become so intense that responsible government was granted. The new constitution set up a bicameral system of upper house appointed for life, and a popular assembly elected for a term of four years to represent the various districts into which the country was divided. The powers of the upper house were more circumscribed than had been the case in the earlier experiments. The party system which obtained in England and elsewhere was introduced and, except for brief periods of coalition governments, remained in force until the suspension of the constitution in 1934.

The chief problems during the half century after the granting of responsible government were: the French shore question, confederation with Canada, transportation (especially building of a railway), chronic unemployment, and financial difficulties.

By the treaty of Utrecht the French had given up territorial claims to the island, but had been granted fishing rights on almost the whole of the northeast and west coasts, which were at that time uninhabited. Settlers in other parts of the island resented this alienation of British territory, and disregarded the laws with respect to both fishing and settlement. Repeated protests to and negotiations with the British government led to certain modifications but no real settlement of the dispute. Indignation became so strong in the 1880's that there was strong agitation for secession from the empire, and union with the United States. After years of frustration an agreement was reached in 1904 whereby the French gave up all claim to Newfoundland, in return for territory in west Africa. This agreement did not affect the status of the French islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon off Newfoundland 's south coast.

At the time of the negotiations which led up to confederation, Newfoundland sent its delegates and for a time it appeared likely that the island would join with the other units which made up the Dominion. However, the appeal to the electorate in 1869 resulted in a decisive defeat for those advocating union. The issue was revived during the financial crisis of the 1890's and again during World War I, but, partly as a result of the apathy of Canada, nothing came of it. Thereafter it lay dormant until 1946.

The problem of providing means of transportation around a rocky coast with a sparse population was one that concerned every government. Construction of a transinsular railway started in 1881 and went on spasmodically, but the bank crash of 1894 led to a cessation of activities. Contracts for completion and operation of the railway were let to Sir Robert Reid, but in 1923 the Reid-Newfoundland Company found itself in financial straits, and to prevent a complete breakdown in the system it was taken over by the government and was operated as a state system until 1949.

Almost every government was plagued by seasonal unemployment and by periodic crises resulting from bad fishing years. The 1860's were particularly bad years, and public relief on a huge scale was necessary. At one time, one-third of the total government expenditure was for able-bodied relief. The economy of the country was so unsound that in 1894 a minor financial crisis in one of the two local banks led to a panic, with the result that both banks failed, and the whole economy of the country came to a standstill.

The period 1880 to 1910, including as it did the settlement of the French shore question, the building of the railway, the financial crises, and the effort to enlarge the country's economy by encouraging mining, agriculture, and other industries, was one of the most significant in the island's history. It is not a mere coincidence that three of Newfoundland's outstanding political personalities emerged during that period. They were, chronologically, Sir William Whiteway, Sir Robert Bond, and Sir Edward (afterwards Lord) Morris.

With the outbreak of World War I, enthusiasm for the British cause ran high, and the island undertook obligations far in excess of its ability. The national debt, which before 1914 was becoming high for the island's small and poor population, increased substantially. In the years following the armistice every government found it necessary to borrow, until, with the onslaught of the depression, the government found itself in the unenviable position of being unable to borrow more money. An appeal was made to the British parliament and the result was a royal commission whose report, made in 1933, recommended the suspension of the constitution and the setting up of a commission to run the country with help from the British exchequer.

The commission of government was created in 1934, and immediately reorganized the civil service. Its attempts to establish land settlements met with indifferent success, but in matters pertaining to health and education there were solid achievements. It was, however, restricted in its scope because of its responsibility to the dominions office in London , and its autocratic complexion was alien to a people ninety-nine percent of whom were of Anglo-Saxon-Celtic stock.

Up to the outbreak of World War II, the government still had to rely on grants-in-aid to balance the budget, but with establishment of defence bases by Canada and the United States , the island enjoyed an unprecedented prosperity. For the first time in many years, able-bodied relief disappeared, and the government was able to announce substantial surpluses year after year.

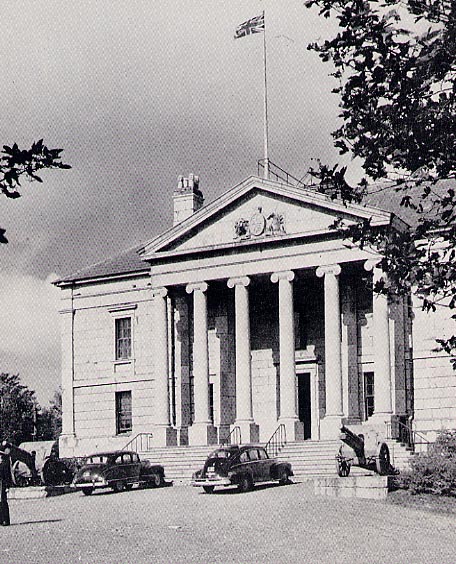

Newfoundland's population is scattered among hundreds

of small settlements mainly along the coast

The terms of the Act suspending the constitution in 1934 had stated that responsible government would be returned upon the request of the people at such a time as the island could be considered self-supporting. With annual surpluses, that condition had been met, and accordingly there was some agitation for a review of Newfoundland 's constitutional position. Thereupon the British government decided that a national convention should be elected to make recommendations regarding the form of government. A majority of the convention favoured restoration of responsible government, but a minority headed by J. R. Smallwood favoured confederation with Canada. A national referendum was held to decide which of the three forms-government by commission, responsible government, or confederation with Canada should be adopted. No one cause received a clear majority, and a second referendum was held with commission of government (which had received the smallest vote in the first) dropped from the ballot papers. In this second referendum the Confederates won by a narrow margin. This victory was essentially the work of Smallwood whose political acumen, inexhaustible energy, and remarkable skill as a debater over-shadowed all the efforts of his opponents.

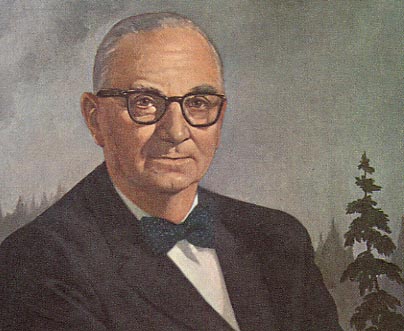

More than anyone else, Joseph R. Smallwood was responsible

for Newfoundland joining Canada in 1949

On March 31, 1949, Newfoundland was admitted into the Canadian confederation as the tenth province. In the provincial election following, the supporters of confederation aligned themselves with the Liberal party headed by Smallwood, and the opponents with the Progressive Conservative party. The election was a complete victory for Smallwood's party, and he thereupon became the first premier of the new province.

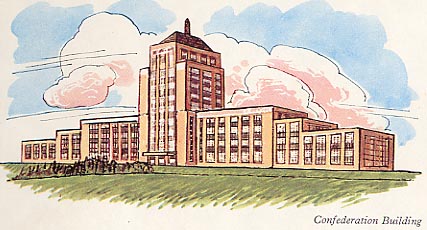

The new Confederation building where the provincial legislature

now debates the great issues affecting NewfoundlandBack to Newfoundland Politics ...

Source: W. Stewart WALLACE, ed., The Encyclopedia of Canada . Newfoundland Supplement , Toronto , University Associates of Canada , 1949, 104p., pp. 43-55, 62-67. Some minor mistakes have been corrected. The text has been reformatted for the web edition.

© 2004 Claude Bélanger, Marianopolis College |