History

|

Newfoundland History |

|

Margarine Madness

[For the source of this document, see the end of the text.]

"Curiouser and curiouser", exclaimed Lewis Carroll's Alice as she became more and more involved in the astonishing machinery of Wonderland. She could say the same about the split decision of the Supreme Court of Canada, upsetting the federal government's 62-year-old ban on the manufacture and sale of margarine.

The court's decision is probably important from a constitutional point of view but it is superfluous from a practical standpoint.

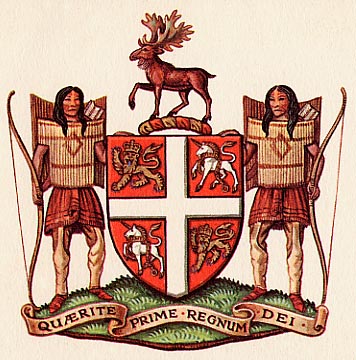

Legality of the sale of margarine in Canada was settled several days ago when terms of union were signed between Canada and Newfoundland.

Those terms included permission for Newfoundlanders to continue making and selling margarine. But they also specifically said Newfoundland mustn't "export" its margarine to the rest of Canada.

How can any government in Canada, federal or provincial, prevent trade between the provinces, in any commodity? It just isn't possible. Several judgments of both the Supreme Court and Privy Council say so. How the federal authorities came to write such a stipulation into the terms with Newfoundland is beyond imagining. But it reveals the state of confusion and bewilderment which the margarine issue has caused in the highest places.

For example, the Chief Justice of Canada vainly tries to uphold the ban on margarine by insisting that margarine is as much a dairy product as butter itself. So he says the power of the Dominion to regulate agriculture have a bearing on the matter.

On that ground a margarine factory is a dairy farm, and a plastics plant which manufactures a wood substitute is, by analogy, a sawmill.

But "curiouser and curiouser", we have opponents of margarine chasing themselves around wondering if the federal government won't appeal the Supreme Court judgment to the Imperial Privy Council. It would require only this to add the last touch of farce to the already farcical situation, for the federal government is generally understood to be opposed to carrying any more appeals to the Privy Council from Canadian Courts. By appealing now, it would be forced to confess it has no confidence in the Supreme Court of Canada.

Canadian agricultural interests, however, have the right to appeal the judgment of the Supreme Court if they want to. But they had best be careful. To launch an appeal while ignoring the Newfoundland position would be futile. For even if they got the ban restored, and the arrangement to permit Newfoundland its margarine still stood, what would prevent Newfoundland margarine from being shipped into every other province?

For that matter, what is there to prevent the Newfoundlanders turning their entire island, and Labrador, too, into a vast margarine factory and shipping their surplus to the rest of us?

Perhaps, however, the Privy Council would uphold the government's antique margarine ban and at the same time upset the Newfoundland agreement on the ground that it conflicts with the original ban. There would be no joke about that.

There still remains the right of any provincial government to enact some sort of legislation to prevent or handicap the making and selling of margarine within its boundaries. How far does such power go? The importation of margarine from other provinces they surely can not prevent, but embarrass it they might.

This part remains to be seen. The test may come very soon, since margarine is expected to be manufactured and on sale in Toronto within a fortnight.

Source : "Margarine Madness", editorial, Vancouver Sun, October 15, 1948, p. 4

© 2004 Claude Bélanger, Marianopolis College |