History

|

Newfoundland History |

|

Military History of Newfoundland

(to 1949)

[This text was written in 1949. For the full citation, see the end of the document. Images, comments under images and links have been added by Claude Bélanger.]

Though Newfoundland was officially claimed in 1583 by Sir Humphrey Gilbert in the name of Queen Elizabeth, still the French, English, Portuguese, and Spanish continued to fish and to dry their catch side by side in the bays and coves of the island, as they had done since the beginning of the sixteenth century, while in other spheres the fleet and armies of their countries warred over the riches of the east and west. Towards the middle of the seventeenth century English and French became dominant: growing numbers of English fishermen and settlers became established on the east and north-east coasts, while the French concentrated in Placentia bay, with fishing-stations in Fortune, St. Mary's and Trepassey bays. In 1662 the French capital was established at Placentia on the east side of the bay, close to the site of the present American naval and air base at Argentia; the area was systematically colonized and strongly fortified, and from that period onwards the succession of Anglo-French wars in India and America had echoes in Newfoundland.

About this time the Dutch made their only bids for the island. Two attacks, one by the celebrated De Ruyter, were made on St. John's harbour in the 1660's, and one against Placentia in 1673.

In 1692 Commodore Williams, and in 1693 Sir Francis Wheler, both homeward bound from the West Indies, detoured into Placentia bay, entered Placentia Roads, and fired a few broadsides into the town; next year an English privateer, Captain William Holman, beat off a French naval attack on Ferryland.

The first major military operation in Newfoundland was the campaign conducted by Frontenac's lieutenant, Pierre Le Moyne, Sieur d'Iberville in 1696-97. While De Brouillon, governor of Placentia , set out by sea, Iberville with regulars, coureurs-de-bois, and Abenaki Indians, to the number of about 500, began a march to St. John's . They made a rendezvous at Renews, and from there began a systematic plundering. St. John's was taken early in January, and then Iberville took his army into Conception, Trinity and Bonavista bays, wreaking havoc. The highlights of this savage campaign was the defense of Carbonear island - the only place that resisted successfully. Iberville returned to Placentia via the isthmus between Trinity and Placentia bays.

In the summer of 1697 a French fleet under Chevalier Nesmond threatened Newfoundland , but the threat was averted by a fleet of twelve or more ships under Sir John Norris, with almost a thousand soldiers on board. By the treaty of Ryswick, France retained Placentia ; nevertheless Norris left a garrison of over 300 men in St. John's .

The opening of the eighteenth century resounded with the din of attacks and counter-attacks. Captain Leake destroyed French fishing stages at Trepassey, St. Mary's, Colinet, St. Lawrence, and other places in 1702, while the French attacked Scilly Cove and Bonavista. During the following year Admiral Graydon made an unsuccessful onslaught on Placentia , and there were new French attacks on Bonavista. These forays against the growing English colony at Bonavista culminated in La Grange 's assault in 1704, which was repulsed by a hastily-organized defence under Michael Gill, a New England skipper, who happened to be in the harbour.

Subercase, governor of Placentia , destroyed St. John's again in 1705, though the forts, commanded by Captains Moody and Latham, did not fall, and many inhabitants were taken as prisoners to Placentia . Montigny and a number of Indians pillaged and terrorized the fishing settlements all that summer. Retaliation was made in 1706 by Captains Underdown and Carleton, and Major Lloyd, new commander of St. John's , against French fishing stations in the north. Two years later, Lloyd and his troops were taken prisoner when St. Ovide destroyed St. John's for the third time in twelve years. A French attack on Ferryland was repelled the same year, and a militia was formed in St. John's . In 1709 Captain Moody was back in command of the capital, and made another raid, in reprisal, on the French fishing fleet in northern Newfoundland waters.

In 1711, the English lost the chance of a lifetime to destroy the French in Newfoundland, when Admiral Hovenden Walker with fifteen ships, mounting 900 guns and with 4,000 regulars in the transport fleet, descended on Placentia, and then withdrew without attacking, though the place was then in sore straits.

By the treaty of Utrecht, 1713, France renounced all territorial claims to Newfoundland, retaining fishing rights only. Placentia was occupied by the English and the inhabitants of that town and the island of St. Pierre deported to Louisburg in Cape Breton . France made a last attempt to control the island in 1762: in June a French fleet under De Ternay; and an army under Comte d'Haussonville, took St. John's for the last time, and Carbonear island for the first time, in the long history of Anglo-French duels in Newfoundland. Trinity also was occupied, and the southern shore pillaged. The French fortified the harbours during the summer and if they had been unmolested that fall and winter, reinforcements would likely have reached them in the spring of 1763 and so caused a protracted struggle before they could be dislodged. However, Sir Jeffrey Amherst acted quickly. He dispatched his brother, Colonel William Amherst, in September, with a fleet and army from New York to St. John's, via Halifax. Amherst landed at Torbay, eight miles north of St. John's, marched overland, captured Signal Hill in a surprise attack, and next day forced the surrender of the lower forts. This was the last military operation that actually took place in Newfoundland .

In the American revolutionary war, when Benedict Arnold threatened Quebec on New Year's day, 1776, the timely arrival of a corps of Newfoundland volunteers under Col. Campbell saved the day. In 1795, the Newfoundland Regiment was established in St. John's, along with several volunteer companies. Next year a fleet of the French Republic under Admiral Citizen Richery burnt Bay Bulls and stood in to attack St. John's. Regulars and volunteers mustered on the hills flanking the Narrows , guns were mounted, and a great show of force made, so that Richery retired.

In 1800 there was a mutiny in the garrison in St. John's; the plot was discovered and the ringleaders hanged. In 1813 the Royal Newfoundland Regiment took part in the battle for York (now Toronto) and other engagements of the War of 1812-1814.

From that time until World War I, no Newfoundland units were engaged in military operations, though numerous individual Newfoundlanders fought in the Crimea, in the American civil war, in South American revolutions, and the Boer war.

In the year 1870, the imperial garrison was withdrawn, and Newfoundland went ungarrisoned till World War II.

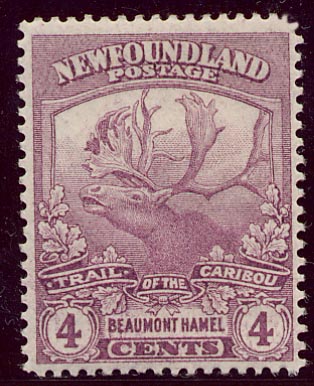

Shortly after the outbreak of World War I, the Newfoundland Regiment was formed. It battle-flags bear the names of many famous and bloody engagements in France , Flanders and Gallipoli, and for its prowess the Regiment was granted the prefix "Royal". It was decimated on July 1, 1916 at Beaumont Hamel on the Somme. here was hardly a home in the island that was unaffected by the carnage of that day, and July 1 is observed as Memorial Day in Newfoundland and Labrador . In addition to those Newfoundlanders who served in army units, were thousands who served in the Royal Navy.

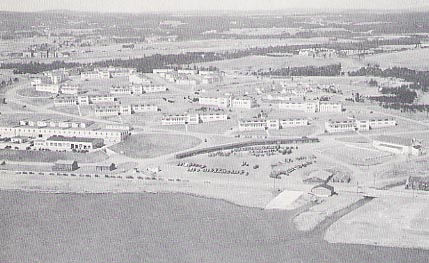

In World War II, Newfoundland became a sally-port for the Allied air and sea forces in the battle of the Atlantic . St. John's was again heavily garrisoned and fortified as a base for convoys, escorts, and striking forces of the Royal and Royal Canadian Navies. When the battle of the Atlantic was at its height, U-boats penetrated Conception bay and sank two iron ore steamers near Bell island. The first United States bases on leased territory in the British Empire were occupied at St. John's, Argentia, and Stephenville early in the war. The great air base at Gander, built by Newfoundland and Great Britain in the 1930's, together with the bases at Goose bay, Labrador, and at Torbay, were vital to the work of ferrying, reconnaissance, and other air operations.

The American base of Fort Pepperell, next to Quidi Vidi Lake,

St John's, Newfoundland, 1944

Two Newfoundland regiments saw action with the Royal Artillery; the 59th Heavy Regiment fought in France and Germany; the 166th Field Regiment in North Africa, Sicily and Italy, coming under the command of Viscount Alexander of Tunis, now Canada's governor general [1949]. In addition, several thousand Newfoundlanders served in the Royal Navy and Royal Canadian and Merchant Navies, in the R.A.F. and R.C.A.F., and in the Forestry Corps in Scotland. About 600 Newfoundlanders were killed in action.

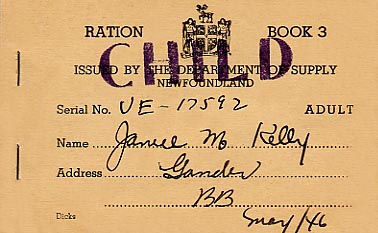

As many other countries involved in the Second World War did, Newfoundland established

rationing to prevent shortages of some products much in demand and to focus the attention of the population on the war. Without it, the war might have seemed remote from the people, with the result that

enlistment might have fallen off.

Since confederation a considerable number of Newfoundlanders have joined the Canadian armed forces, and a branch (21st) of the Canadian Naval Reserve, was formed recently in St. John's.

Bibliography. Early military history of the island is dealt with in the histories of Newfoundland by L. A. Anspach (1819), R. M. Martin (1844), C. Pedley (1863), D. W. Prowse (1896), and J. D. Rogers (1911). More recent events are covered in L. C. Murphy, Newfoundland's part in the Great War, in J. R. Smallwood (ed.), Book of Newfoundland (St. John's, 1937); R. A. MacKay (ed.), Newfoundland: economic, diplomatic, and strategic studies (Toronto, 1946).

Back to Newfoundland politics ...

Source: W. Stewart WALLACE, ed., The Encyclopedia of Canada. Newfoundland Supplement, Toronto, University Associates of Canada, 1949, 104p., pp. 43-55, 62-67. Some minor mistakes have been corrected. The text has been reformatted for the web edition.

© 2004 Claude Bélanger, Marianopolis College |