History

|

Newfoundland History |

|

Newfoundland History

The French Occupation and the French Shore of Newfoundland

[This text was written in 1950. For the full citation, see the end of the document. Links, the comments in brackets [...] and the image have been added to the original by Claude Bélanger. For further information on this issue, consult this page.]

One of the first problems to confront Newfoundland in the early days of responsible government was the difficult and complex question of the fishing rights on the coast of Newfoundland which had been accorded to France by Great Britain in a series of treaties in the 18th and early 19th centuries. The first of these was the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, under which the French recognized the sovereignty of Great Britain over Newfoundland but retained certain fishing rights on a specified section of the coast, from Cape Bonavista around the northern tip of the Island to Point Riche on the west coast. On this part of the coast they were permitted to "catch fish and dry them on land", a right which was confirmed in the Treaty of Paris, 1763. Disputes soon developed as to the precise extent of the French shore and in the Treaty of Versailles, 1783, the limits of the French shore were changed so as to extend from Cape St. John on the northeast coast northward and along the whole of the west coast to Cape Ray. The rights were still confined to the catching of fish in territorial waters and drying fish on land and did not permit the French to erect buildings, save the huts necessary for the prosecution of the fishery, nor to winter on the Island.

The terms of these treaties were, unfortunately, ambiguous enough to permit different interpretations. The British Government held that British subjects had concurrent fishing rights on this part of the coast so long as they did not interfere with the French fishery; the French Government claimed exclusive use of the treaty shore. These different interpretations led to repeated negotiations between the French and British Governments and to constant and bitter conflicts between French and Newfoundland fishermen. A crisis was reached in 1857, when the British Government drew up a convention in which it recognized the French claim to exclusive use of the treaty shore. When the convention was placed before the Newfoundland legislature, this body adopted vigorous resolutions of protest and appealed to the mainland colonies for their support on the issue, which was believed to be a matter of constitutional right. In the face of Newfoundland 's determined opposition the British Government, in the famous "Labouchère Despatch", reviewed its position and gave assurance that the British Government considered the consent of the community of Newfoundland to be "the essential preliminary to any modification of their territorial or maritime rights". The Labouchère Despatch has been prized as the Magna Carta of Newfoundland , guaranteeing it against Imperial encroachment.

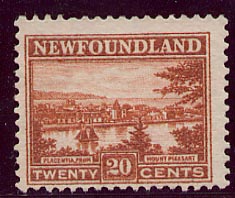

The basic conflict between French claims to exclusive rights and Newfoundland claims to concurrent fishing rights and to settlement on the treaty shore was still not resolved. In 1872 Newfoundland won the right to appoint magistrates on the west coast, to grant land for mining and agriculture, and to representation of the inhabitants of the west coast in the Newfoundland legislature. At length, in 1904, as part of a general settlement of outstanding territorial issues, the British and French Governments entered into a general convention by which the French gave up their claims to an exclusive right of fishery in Newfoundland waters in return for territorial concessions in Africa. Thereafter the western and northern coasts were open to unrestricted settlement and development by Newfoundlanders. [For a history of the French settlements in Newfoundland, consult this page.]

Source: GOVERNMENT OF CANADA , Newfoundland . An Introduction to Canada's New Province, Published by authority of the Right Honourable C. D. HOWE, Minister of Trade and Commerce, prepared by the Department of External Affairs, in collaboration with the Dominion Bureau of Statistics, Ottawa, 1950, 142p., pp. 15-41.

© 2004 Claude Bélanger, Marianopolis College |