|

|

| Date Published: |

L’Encyclopédie de l’histoire du Québec / The Quebec History Encyclopedia

History of the Canadian Boundaries

[This text was written in 1948. For the full citation, see the end of the document. The claim of the editor that the British authorities defended strongly Canadian interests in the border issues between Canada and the United States is highly questionable. Clearly, in some cases, the British negotiated with highly aggressive American authorities who threatened war if they did not get their way. Such was the case in the Oregon and Alaska disputes. Few in the British government thought that defending Canadian territorial claims was worth a war with the rising power of the Americans.]

The present boundaries of the Dominion of Canada are the result of a long evolution, in which (against a background of imperfect maps and geographical ignorance) wars and rumours of wars, international negotiations, treaties, and arbitrations, and judicial decisions have all played their part. During the French regime, very little attempt was made to define the boundaries of New France and Acadia at all. Their boundaries were what the French were able to make them. New France or Canada included the whole of the valley of the St. Lawrence, and extended even to the valleys of the Ohio, the Mississippi, and the Saskatchewan; and the lines which marked off Acadia from New England, on the one hand, and from Canada, on the other, were never precisely drawn, either before or after the province passed by the Treaty of Utrecht into British hands, and became Nova Scotia. It was only after the fall of Canada in 1763 that the first precise definition of boundaries took place; and the province of Quebec, which was created by the Royal proclamation of October 7, 1763 , comprised only a small part of what had been New France . The new province was bounded on the east by the river St. John; thence the boundary ran from the head of that river through lake St. John to the south end of lake Nipissing, and from this lake in a south-easterly direction to a point where the 45th parallel of latitude intersected the St. Lawrence river; thence it followed the 45th parallel to the height of land south of the St. Lawrence, and passed along the height of land until it reached the Restigouche river and Chaleur bay. By the Quebec Act of 1774 these boundaries were greatly extended. Labrador was annexed to Quebec on the east; and on the west the boundary followed the south shore of the St. Lawrence, lake Ontario, and lake Erie to a point where it was intersected by the boundary of Pennsylvania; this it followed until it struck the Ohio river; and then it ran along the Ohio river to its mouth, and up the Mississippi river to the southern boundary of the territories granted to the Hudson's Bay Company. Quebec thus came to include, not only Labrador and a large part of what is now Ontario, but also the whole of what is called the "Old North West", including the western lake posts. During the American Revolution, the British lost control of most of the "Old North West"; and by the Peace of Paris in 1783 this territory was surrendered to the Americans, though the British retained temporary possession of the western lake posts until 1796.

It was the British and American negotiators of the Treaty of Paris in 1783 who determined, in its main outlines, the southern boundary of what was to become in 1867 the Dominion of Canada. Relying on the famous Mitchell map of 1755, they defined the boundary as running from the mouth of the St. Croix river, on the bay of Fundy, to its source, thence along a line drawn due north to "the north-west angle of Nova Scotia", thence along the highlands dividing the rivers falling into the Atlantic from those falling into the St. Lawrence, to the north-westernmost head of the Connecticut river; down the middle of that river to the 45th degree of north latitude, and along this parallel of latitude to the St. Lawrence river; thence up the middle of the St. Lawrence, through lake Ontario, the Niagara river, lake Erie, the water communication between lakes Erie and Huron, lake Huron, lake Superior, and so to Rainy lake and the lake of the Woods, and from the most north-western point of the lake of the Woods "on a due west course to the river Mississippi." Unfortunately, the map on which they relied was most inaccurate; and the language of the treaty proved for many years a fertile source of dispute - dispute which threatened on several occasions to develop into actual war.

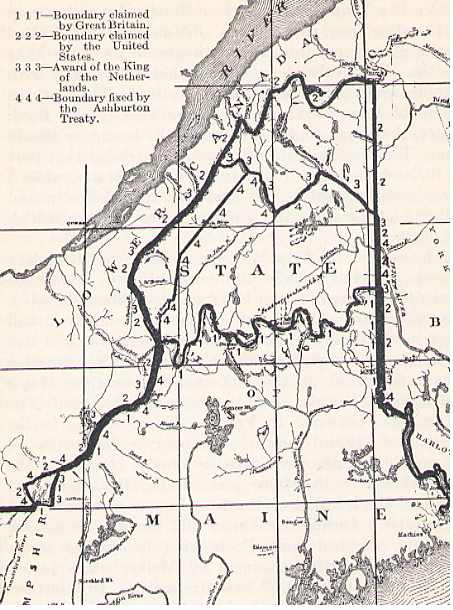

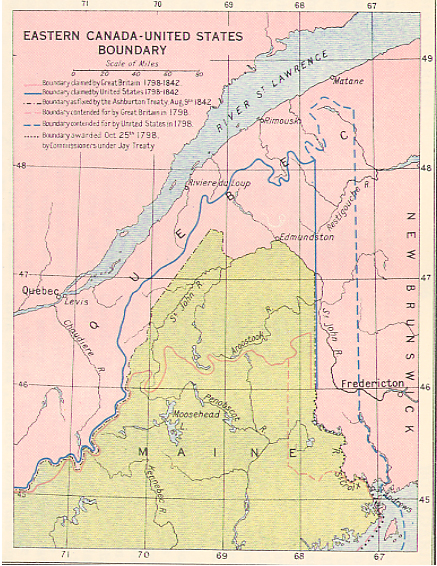

The Eastern or Maine Boundary.

The first difficulties arose in connection with the western boundary of New Brunswick , or (as it came to be known, after Maine was created a state in 1820) the Maine boundary. The question arose as to what was the "St. Croix river" mentioned in the Treaty of Paris. There flowed into Passamaquoddy bay no less than three rivers, any of which might reasonably be regarded as the St. Croix river of the early maps, and it was difficult to determine which of these was meant by the commissioners of 1783, especially as the Mitchell map showed only two of these rivers. The matter was referred in 1794 to a joint commission, which came to the conclusion, in 1798, that the river meant was that now known as the Schoodic. This river, however, had two branches, the western, known as the Schoodic, and the eastern, known as the Chiputneticook. The majority of the commissioners first favoured the western branch, but there was some doubt as to its real source; and in these circumstances, as a compromise, the Chiputneticook was chosen. But the difficulty did not end here. The only highlands reached by a line drawn due north from the source of the Chiputneticook were those marking off the watershed of the bay of Chaleur; and a line drawn north to these meant the virtual severance of land communication between the maritime provinces and Quebec - a solution which the British government was loath to accept.

Claims and counterclaims in the Maine/New Brunswick boundary Webster/Ashburton settlement of 1842

In 1814 the identification of the highlands in question was referred by the Treaty of Ghent to a joint commission; but the commissioners were unable to reach a joint decision. After the state of Maine was created, the situation became acute; and in 1831 an attempt was made to settle the dispute by referring it to the arbitration of the King of the Netherlands, who found that no line actually fulfilled the terms of the treaty, but who suggested a compromise. This suggestion the British government was prepared to accept; but it was rejected by the government of the United States, who maintained that the King of the Netherlands had exceeded his instructions in making it. The dispute therefore dragged along until 1841, when Daniel Webster, the American secretary of state, proposed its settlement by direct negotiation. The British government appointed Lord Ashburton to conduct the negotiations; and he and Daniel Webster arrived in 1842 at a compromise, known as "the Ashburton award" [or Webster-Ashburton Treaty], which placed the boundary south of the line claimed by the United States, but north of that claimed by Great Britain. The compromise was unpopular on both sides. Daniel Webster was attacked on the ground that the award was "a British victory"; and Lord Ashburton was accused of having betrayed the interests of the British North American colonies. In fact, the idea, long entrenched in Canadian minds, that Great Britain has consistently sacrificed Canadian interests in her negotiations with the United States, dates from this time. But the verdict of the best modern scholarship seems to be that Lord Ashburton obtained for Canada in 1842 all that could be expected in the circumstances, and perhaps more.

The Western Boundary.

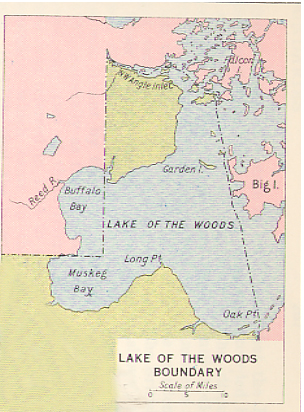

A further difficulty arose in the determination of the language of the Treaty of Paris. According to the treaty, the boundary was to run from the north-westernmost point of the lake of the Woods due west to the Mississippi; but a line drawn due west from this point on the lake of the Woods does not touch the Mississippi, since this river rises farther south. Fortunately, this mistake was soon discovered; and in 1818 it was agreed that the boundary should be drawn from the lake of the Woods along the forty-ninth parallel of latitude to the Rocky mountains .

Lake of the Woods boundary decision (1818)

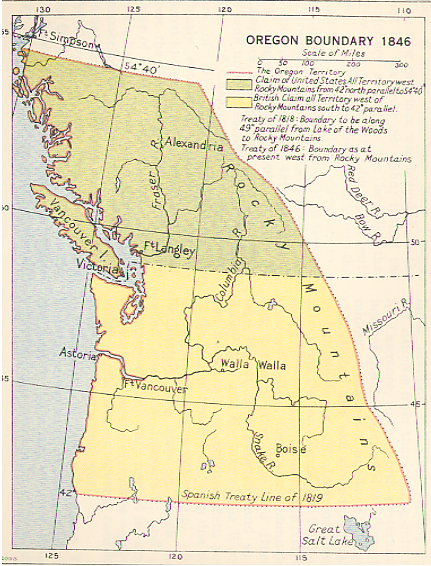

The Oregon Boundary.

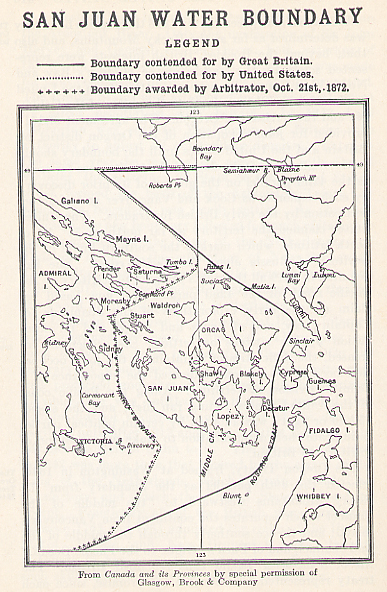

The agreement of 1818, however, left unsettled the question of the boundary from the Rocky mountains to the Pacific coast. The United States proposed in 1818 that the boundary line should follow the forty-ninth parallel of latitude to the coast; but this line would have robbed Great Britain of what was known as "the Oregon country", of which the Hudson's Bay Company was at that time in possession. It was true that an American ship had, in 1792, entered and explored the mouth of the Columbia river, and that in 1811 J. J. Astor had established here a trading-post, named Fort Astoria. But Captain James Cook, a British navigator, had explored the whole of the Pacific coast in 1778; and in 1813 Fort Astoria had been handed over to the Canadian North West Company. As a temporary solution of the dispute, it was agreed that the Oregon country should be occupied jointly by Great Britain and the United States for ten years; and in 1827 a convention was concluded whereby the joint occupation was extended indefinitely, subject to its termination by either side on one year's notice. About 1843 matters came to a head with the influx into the Oregon country of a large number of American settlers. These enlisted the sympathy of their compatriots in the east; and in 1844 the national convention of the Democratic party in the United States passed a resolution which was interpreted as claiming for the United States the whole of the Pacific slope as far north as 54' 40" north latitude, the southern boundary of the Russian territory of Alaska . "Fifty-four forty or fight" was the battle-cry of the Democratic party in the elections that followed. But fortunately war-like feelings on both sides were overruled, and in 1846 a basis of agreement was reached in the Oregon Treaty. Under this treaty it was arranged that the boundary should follow the forty-ninth parallel from the Rocky mountains as far as the middle of the channel that separates the mainland from Vancouver island, and thence southerly through the strait of Juan de Fuca to the Pacific ocean. This meant that Great Britain lost the lower Columbia valley, but retained the whole of Vancouver island. The exact line of the water boundary was not clearly defined, and for many years the ownership of San Juan island was in dispute. But in 1871 the ownership of this island was referred to the arbitration of the German Emperor, and by him it was awarded to the United States.

Oregon territorial dispute and settlement (1846)

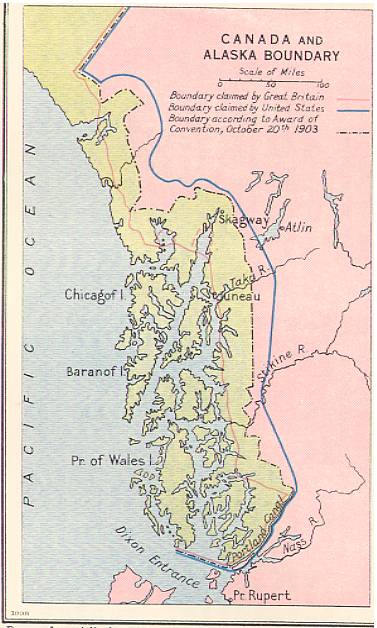

The Alaska Boundary.

Thirty years after the San Juan award, another boundary dispute occurred with the United States. This was the dispute over the Alaska boundary. The United States had purchased Alaska from Russia in 1867; and in 1825 the boundary between the Russian and the British possessions in North America had been decided by giving to Russia the coast line, from Prince of Wales island northward, for a distance of "ten marine miles inland." What was meant by the phrase "ten marine miles inland" was a matter of interpretation; but no difficulty would perhaps have occurred had not gold been discovered in 1898 in the Klondyke. The miners flocking into the Klondyke from the coast had to pass through a fringe of American territory; and naturally difficulties arose. In 1903 the question of the Alaska boundary was referred to a joint commission which was to be composed of "six impartial jurists of repute". The president of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt, unfortunately appointed to represent the United States on this occasion at least two commissioners who could not be described as impartial, since they had already expressed publicly their opinions in regard to the matter in dispute; and from the first it was clear that the American commissioners were not prepared to agree even to a compromise. In the end, in order to avert war, Lord Alverstone, the British commissioner, was compelled to defer to their views. The two Canadian commissioners dissented from the award; and there was in Canada great indignation over what was regarded as the betrayal of Canadian interests by Lord Alverstone. The United States obtained, not only the boundary line it claimed, but also two small islands, the only value of which was that they were thought to command the entrance to the terminus of a projected Canadian railway. It was regrettable that the United States should have referred to arbitration a matter she was apparently unwilling to refer to "six impartial jurists of repute", and in particular that she should not have been willing, for the sake of international good feeling, to abandon her claim to the small islands in question. But the idea that Canada could have obtained in 1903 better terms by direct negotiation than by arbitration is most improbable; and the impression, still widely prevalent in Canada, that Canada has been consistently betrayed by Great Britain in the boundary negotiations, seems to be without basis in fact.

Alaska Boundary dispute and settlement (1898-1903)

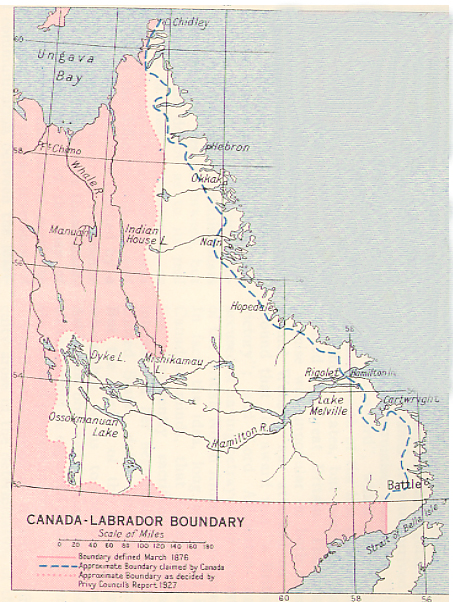

The Labrador Boundary.

The most recent of Canada 's boundary disputes has been, not with the United States, but with Newfoundland. In 1825 the old province of Canada concluded with Newfoundland an agreement whereby Canada ceded to Newfoundland the "coast" of Labrador. Just what was meant by the "coast" of Labrador long remained in doubt. Canada maintained that it meant the "fishing coast", in which Newfoundland was in 1825 exclusively interested; but after 1903, when the pulpwood and water-powers of the interior of Labrador began to have a commercial value, Newfoundland pressed the view that the word "coast" meant the watershed lying back of the coast-line. The dispute was finally, referred to the judicial Committee of the Privy Council; and in 1926 the case was argued at great length by the legal representatives of Canada and Newfoundland . In 1927, the judicial Committee of the Privy Council found, with some slight reservations, in favour of Newfoundland's claim. The boundary between the province of Quebec and Newfoundland was defined as running along "a line drawn due north from the bay or harbour of Blanc Sablon as far as the 52nd degree of north latitude, and from thence westward along that parallel until it reaches the Romaine river; then northward along the right or east bank of that river and its headwaters to their source, and from thence due north to the crest of the watershed, or height of land there; and from thence westward and northward along the crest of the watershed of the rivers flowing into the Atlantic ocean, until it reaches cape Chidley."

Labrador boundary dispute and settlement (1927)

For a discussion of the disputes relating to the boundaries of Canada, see H. L. Keenleyside, Canada and the United States (New York, 1929) and J. White, "Boundary disputes and treaties", in A. Shortt and A. G. Doughty (eds.), Canada and its provinces, vol. viii (Toronto, 1914).

Source : W. Stewart WALLACE, ed., "Boundaries", The Encyclopedia of Canada , Vol. I, Toronto, University Associates of Canada, 1948, 398p., pp. 265-269. |

© 2005

Claude Bélanger, Marianopolis College |

|